Submitted by Jamy Ian Swiss on

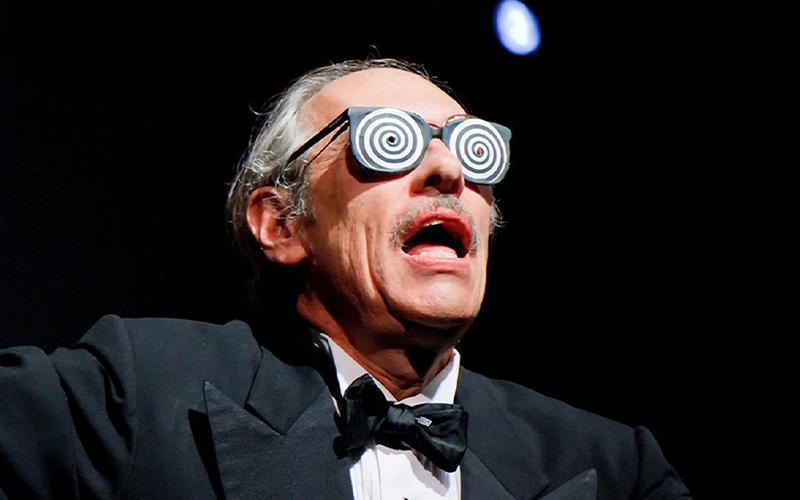

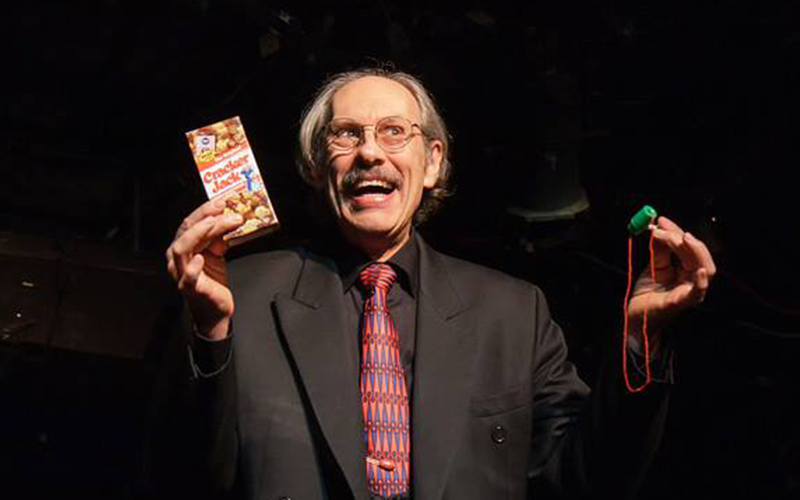

Peter Samelson

In 1976, I saw ten minutes of close-up magic that would, literally, change my life. I was at the annual Tannen’s Magic “Jubilee” conference, which I had attended regularly from my early teens through to my late twenties. I had been performing magic since about the age of seven, and the notion of ever becoming a professional magician—a step I would not take for another twenty-two years—was still far from my consciousness.

The performer I saw was unknown to most at the time, if not to all of the convention goers—myself included. But at the conclusion of his brief performance, I knew I had seen something unique—something special. Yes, I had seen some beautiful, deceptive and original magic, but above all, I had just witnessed a performer with a distinct point of view. Far from the frequent stuffiness or awkwardness that comprised so much of magic, here instead was a young man of my own generation who demonstrated, in the words and attitude of his work, that he not only knew what year it was, he knew which day it was. The magic, and the person behind it, was, in a word, contemporary. Peter Samelson’s material was also contemplative, reflecting clever elements of wordplay and interesting subject matters that were not typical of magic of that time. There was a touch of humanity and a presence of “real life” in the work: a round of applause for his mom, a card trick about a classic sci-fi movie. Peter made magic… relevant.

As I watched his performance, it seemed to me that Peter Samelson had found the answers to questions that had long nagged me about magic, but that I had not yet clearly formulated. I sought him out at the convention, and we had a snack in the the hotel’s coffee shop.

I then spent the next year trying to get him to come to dinner.

Peter has a theater degree from Stamford, and being “a theater guy” had contributed significantly to his distinct point of view about magic. It also meant that, at that point in his developing career, he was resistant to hanging around with magicians. So while I would chase down any opportunity to see him perform—several times in Manhattan at the Magic Town House, the premiere New York close-up magic venue of the Seventies—every time I invited him to my place, he would gently demur.

On one occasion, I learned that he was performing in Brooklyn at the opening of a bank. (Hey, it’s show business; we were young—don’t judge!) I managed to navigate my way to the venue and found him performing out in the parking lot. Needless to say, he was surprised to see me. But he was even more surprised when I gave him a hand-lettered invitation, artfully adorned with elegant calligraphy—courtesy of a friend of mine—on a piece of faux parchment paper that had been burned around the edges (Tony Andruzzi would have been proud), asking him to come to dinner, at the home I shared with my then-wife, in Brooklyn. He really couldn’t refuse; and for better or worse, he accepted.

And thus began my friendship with Peter Samelson; an association of more than forty years now that has born fruit in countless ways—personally, creatively, and in work and business.

In our early meetings, Peter schooled me in his theatrical and conceptual approach to magic, explaining the questions he asked himself about every new routine: Who? Who are you, the magician? Who is your audience? What? What are you doing? And why? Why are you doing it? These, and countless other ideas, were completely new to me, but they would become deeply integrated and influential in my work. He also taught me about taste, in lessons both large and small—including, in one memorable moment, when I learned from him what “too dead on” meant: Such as, why you don’t put little googly eyes on sponge balls, when their neutrality as a simple, and hence recognizable, universal form renders them far more useful in metaphorical roles.

It didn’t take long for the learning process to become a two-way street. At the time, Peter was already an accomplished professional close-up magician, and he was in the early stages of developing a stage repertoire. He was working with a theatrical director as well—a notion that had never even occurred to me—and I joined in on their writing and directing sessions on a regular basis. Serving initially as a technical consultant for the magic, my role gradually expanded as a writing brainstormer and collaborator. Eventually, I would become Peter’s stage director for one of his ambitiously themed stage shows; and for a time, his business manager, too. All of the work comprised a challenging and advanced learning process for us both.

When I met Peter, I was working in Manhattan, where I was a part owner and operator of a small telephone company that provided telephone systems to small businesses. In the evenings after work, I would leave my midtown office and often make the short trip to Peter’s loft in Chelsea, where we would talk endlessly… about magic, the arts, our lives. Among the many lessons inherent in those untold hours, I also had my first chance to witness the life of a professional magician up close. Until then, the notion of finding a profession in the arts wasn’t even a fantasy, much less something about which I possessed any practical insight. It was worlds away from the life I grew up in, and hardly one I had ever anticipated for myself.

But seeing such a life firsthand made it suddenly take shape as a reality, and as a real possibility. A few years later, not long after Peter moved on to bona fide artistic management, and after I moved out of the phone business, I began casting around for ideas about my next professional incarnation. That’s also when my wife, who had a successful career in the medical world, said: “If you don’t try it now, you’re always going to wonder what might have been. And if it doesn’t work out, you’re still young enough to go do something else.” While that is not the story to tell here, I will say that in many ways it was Peter’s life that both freed and inspired me to become a professional magician in 1981.

Those were just the beginnings of our longstanding connections and intertwinements. In 1982 I wrote the preface for and edited his book of close-up magic, which first appeared as a comb-bound edition entitledSensations, and then subsequently as Theatrical Close-up when it was published in 1984 by Mike Caveney’s “Magical Publications.” The book has long been out of print, but it found a cult following. In it, Peter presented many of his ideas about theater and magic, and included instructions for a wonderful assortment of original close-up magic, including two routines I’d seen that day in 1976 at Tannen’s “Jubilee.”

In the early Eighties we also spent a great deal of time with our mutual pal, Geoff Latta. The three of us would collaborate and shoot a video that would become an underground legend of sorts, known as the Pink Purse Tape, that captured some of Latta’s close-up card and coin work. Recently, I served as editor on the long-awaited book of Latta’s coin material—The Long Goodbye, by Stephen Hobbs and Stephen Minch—that was published last year. We are currently working on a similar volume of Latta’s card material, where the full story of the notorious tape will at last be recounted; a copy of which will also accompany the book (a portion was included on video with the coin book).

Around and through the other interweaving tales, it was Peter who mentioned my name to Bob Sheets when they were both competing at the Desert Magic Seminar Close-up Contest. That introduction would lead to my auditioning at the Brook Farm Inn of Magic, where, in 1985, I was eventually hired as the Magic Bartender for the new and expanded location, the Inn of Magic—a formative point in my career.

And in 1997, Peter would get a call about a newly started show in New York City called Monday Night Magic. He, in turn, referred that call to me, and I called Todd Robbins. Eventually we would all become co-producers of what is today New York’s longest-running Off-Broadway show, now in its twenty-first continuous season.

As someone once said: “What a long strange trip it’s been.”

I used to say that Peter Samelson is the most influential magician you've never heard of. While many more magicians have heard of him these days—thanks to an assortment of awards, international lectures, a huge variety of venue appearances, and features in magic magazines, among other recognition and accolades—Peter's influence remains ever further reaching. Because he was so ahead of his time in his thinking about the presentation and performance of magic, many of his ideas are now seamlessly incorporated as part of modern changes in attitude among magicians, without any awareness that Peter had a hand in those shifts within the art and the culture of magic.

While the trick known as the Snowstorm in China has become ubiquitous, it was Peter’s first scintillating presentation that transformed the piece from a pretty flourish into an emotional and theatrical wonder. Peter influenced other magicians who would later incorporate story presentations and personal narratives about childhood into their performances of that piece, including, no less, than the likes of David Copperfield.

Although I usually avoid press-clip promotion in these Take Two essays, I’ll make an exception here, because the New York Times, many years ago, offered a succinct pull-quote profile when they dubbed Peter, “the soft-spoken conceptualist of magic.” I couldn’t have said it better myself. The description is apt in more ways than one.

Among his many credits and productions, Peter has created and produced two original Off-Broadway shows. One was called Paperworks, in which every routine had something to do with the use of paper. The other was the one I helped to direct, lo! those many years ago, called Standing Up and Looking Ahead. While it was an autobiographical piece, it wasn’t done in a first-person literal manner, as is so often attempted and so hard to execute effectively, but rather as a metaphorical version, using stories, images, and magic in new ways to which audiences could truly relate. The show was stunningly original and, occasionally, provocative. At the close of the first act, for example, Peter attempted a straitjacket escape that would eventually fail, leaving him passed out and still, fallen to the stage, throughout the entirety of the intermission. It was a great experience to watch, and to feel, the audience’s reaction to such a visceral display for the next fifteen minutes. Eventually, at the top of the second act, he would manage to escape.

Perhaps Peter’s widespread influence is perfectly captured in a routine I cannot show you here because there is no publicly posted video. In it, Peter performs the classic illusion known as the Torn & Restored Thread. Long before Eugene Burger created his signature version of this routine, which is accompanied by the Hindu creation myth, Peter created his own profoundly emotional and universally human version, which used the illusion as a visual metaphor for a simultaneously serious, witty, and authentically personal commentary on relationships. It is a piece that is, in every sense—like Burger’s—considered to be a true, modern classic.

Since the early twentieth century (certainly since the publication of Our Magic by Nevil Maskelyne and David Devant, which I referenced in the preface to Theatrical Close-up), there has been much discussion in the world of magic as to the nature of magic as an art. Some even debate whether magic is or isn’t art—a question I find silly, but frequently muddied by the notion that “art” must indicate some indefinable measure of “good”—and in my opinion, it is an utterly misguided pursuit. Art is simply creativity as self-expression, and good or bad are infinitely subjective and arguable aspects that we can, and will, debate until the end of our species.

But while I read about the idea of magic as art in Our Magic, and was provoked by the claims and discussion I first found there, it was in meeting Peter that I became convinced that magic should be treated as an art form, and that it can be explored and expressed as such by the best performing artists in the field. Peter set an example for me in terms that I could learn from—and in terms I still think about today, in every aspect of my work.

I hope you enjoy the examples that follow of the distinctive art and artistry of Peter Samelson’s magic.

Peter Samelson

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

We begin with one of the two routines I first saw Peter perform. While the original movie remains a classic and has assured that this piece has never become dated, the hipness factor of talking about this film in the Seventies gave the piece extra frisson at the time.

—♦—

Mimetic Slo-Mo Performance

Here’s a lovely bit of sleight-of-hand magic that simultaneously reflects Peter’s theatrical thinking and training, while also revealing elements of Geoff Latta’s technical influence.

—♦—

Ring & Rope and Rose

This next routine is a longstanding staple of Peter’s repertoire. It reflects solid magic, good routining, and his typical mix of charm and playfulness. Truth be told, while this has been Peter’s preferred version of this routine for many years, it’s actually a mashup of a wonderful close-up routine and what was an original, separate stage routine that eventually became the climax to this version. Either way, it’s a textured and varied piece of magic, founded in classics but made newly modern, shaped by a distinctive artistic voice.

—♦—

Lady Fair & Mr. Smooth

Not unlike Body Snatchers, this routine also retains its performing relevance thanks to the universality of its themes, but when it was first created it possessed a definite, if playful, edge in its invocation of issues of women’s equality in relationships. (I recall the original version including a reference to Edna St. Vincent Millay, definitely an unexpected moment in a magic routine of the era.)

—♦—

Snow

And finally, here is one of Peter’s true masterpieces, likely his most famous routine in the magic world. It is a perfectly seamless blend of illusion and presentation, providing a visual and magical metaphor that renders it effortless for the audience to apprehend—an artistic accomplishment far more often attempted than achieved. So many efforts at this kind of work fail because the linkage is forced.

Here is a model, and the proof, if indeed we need it, that magic is an art.

And…

Getting Absorbed in the Times

Here’s a little something extra if you’re so inclined. This is an ambitious stage piece circa 1987 that, again, reflects the wide expanse of Peter’s playful creativity. With advance apologies for the poor quality of the recording and the overlay of the Japanese television narration, this remains a unique piece of truly theatrical stage magic.

SEE TAKE TWO INDEX