Submitted by Jamy Ian Swiss on

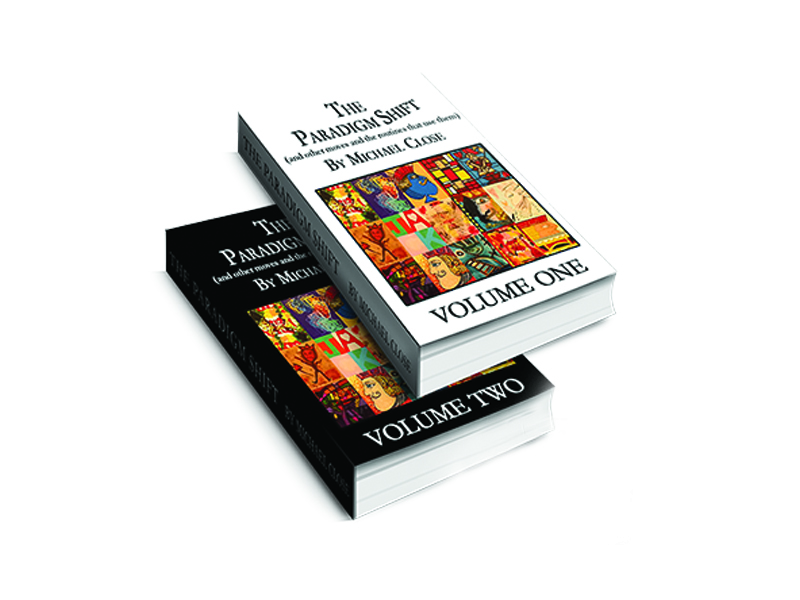

The Paradigm Shift

Volumes One and Two

by Michael Close

Book Review by Jamy Ian Swiss

Okay, so it’s not like Michael Close had vanished from the magic scene. Far from it, since among other things, he’s only just recently retired from his post as Editor of M-U-M. magazine for the past nine years, and has been serving as a Consulting Producer for the past four seasons on Penn & Teller: Fool Us series (which is shooting as I write this).

But it’s been awhile since we’ve had a book from Mr. Close, his last being Closely Guarded Secrets in 2006, a trailblazing ebook that incorporated embedded video clips that demonstrated the appearance of various moves and techniques described in the text.

While Mr. Close will need no introduction to his contemporaries, I will say a bit more about him for those who may be just discovering his work, since increasingly I come across younger magicians who seem to mostly be familiar with names of young producers of instant download tricks, and who seem to believe that watching a video of an ill-informed magic enthusiast “reacting” to magic on television is somehow a useful way to learn something about magic (that he mostly doesn’t understand himself). As David Malek writes in his recently released Dream Card Revisited, regarding the current ready access to the work of sleight-of-hand experts like John Carney, Michael Weber, and Steve Forte, “…if you pared down the people whose work you study, not only would you eliminate a lot of wasted time, but you would become a much better magician and in very short order at that.”

Michael Close has in his lifetime in show business, worked extensively as both a professional magician and a professional musician (he plays piano). At one time a professional restaurant worker in his native Indiana, Michael was mentored by legendary sleight-of-hand maestro (and jazz radio program host) Harry Riser, whose own two closest mentors were no less than Charlie Miller and Dai Vernon. The late Mr. Riser has also long been named as mentor to Johnny Thompson; despite their closeness in age, it was Riser who helped guide Thompson toward the kind of magic that would eventually lead to his becoming the legendary master he is considered today. In other words, Mr. Close is part of a lengthy and honored continuum of great magicians, a line he has done great justice to by continuing to contribute in creative and generous manner for future generations. He has not missed the true lessons of his mentors.

I first met Mr. Close in the late 1980s when he was a full-time performer at Illusions, an upscale magic-themed restaurant in the suburbs of Indianapolis, and where in the course of a couple of years I performed periodically. In the midst of Mr. Close’s varied and well traveled career, ended up living in Las Vegas for an extended period, where he performed as sole resident magician in the Houdini Lounge in the Monte Carlo Hotel & Casino (where Lance Burton, at his eponymously named theater there, performed his full evening show from 1996 until his retirement in 2010).

Mr. Close also notably served as product reviewer for MAGIC magazine circa 1995 through 2005, where he regularly exemplified the kind of erudition, expertise, taste, and courage required in order to provide invaluable guidance in the tradition of genuine criticism. And he has also produced several marketed routines and a number of instructional videos. But it’s fair to suggest that his most notable achievement for magicians was his authorship of the Workers series, Volumes One through Five, from 1990 through 1996. These “inexpensively produced and premium-priced manuscripts” served in their initial iterations to firmly establish Mr. Close as one of the premier close-up magic thinkers and creators of his time.

I am a huge fan of the Workers series, as I have widely and repeatedly proclaimed throughout my writings, reviews and teachings over the years. Indeed, when last year I wrote a lengthy piece about recommended reading for magicians for Aaron Fisher’s “Conjuring Community” website (discreetly entitled by the publisher, 30 Magic Books That Can Change Your Life: Your Ultimate List), I wrote:

The Workers Series by Michael Close is every bit as important a contribution to the literature of magic as is The Books of Wonder (by Tommy Wonder and Stephen Minch), and would have readily been recognized as such had the entirety been issued all at once in substantially produced volumes like The Books of Wonder, rather than over a period of years in five comb-bound installments. The Workers books are loaded with useful close-up material, both card and non-card, and serve as extraordinary teaching manuals of how to select good effects, sound methods, and smart construction, accompanied by creative presentations that are delightfully and sufficiently eccentric as to serve as good teaching examples but that won’t readily fit most other performers – an excellent state of affairs from which to learn how to become one’s own unique artist. And beyond all of this, the Workers books are probably the best examples in the entire literature of close-up magic of the art of routining magic – of building entertaining multi-phase and multi-faceted routines out of individual, integrated effects. This is the kind of magic that entertains audiences, holds their attention, and from which you can build a magic show – not merely a quick shock or a stunt, or a reality TV spot.

That is well worth repeating for anyone who does not yet have a set of these books on their shelves. In 2005 the entire set was re-released in ebook form by Mr. Close. It’s an easy matter to have those ebooks printed and bound at your local copy shop – which I did upon their release, despite owning a set of the originals – and I highly recommend your doing so. And you can also purchase a 650-page softbound single volume version from Mr. Close’s website. But I, for one, still hope that we shall someday see a beautifully two-volume hardbound collection of these timeless books, which deserve a place on every magician’s shelf of modern classics.

In Closely Guarded Secrets in 2006, Mr. Close presented readers with a volume of material that he had developed primarily in his years of performing in the Houdini Lounge, where both the conditions and the patrons differed significantly from those he had previously encountered in Indiana restaurants. Accordingly, the author had gradually developed a new repertoire better suited to both the new conditions, as well as being more reflective of the man and the artist who was performing those routines at the time. Mr. Close wrote about the fact that as part of that evolution, he found himself leaving most of his older repertoire behind him, since much if not most of it felt increasingly ill-suited not only to the setting, but to the artist.

As life would have it, Mr. Close has been through another set of life changes in the 13 years between that last book and these new releases, including marriage, several relocations that have concluded with him residing for some years now in Toronto, Ontario, and – certainly by no means least of all this – having adopted a daughter in 2007, who at this writing has grown from her adoptive infancy into a young adolescent, and budding singer and actor. And, too, as already mentioned, through the past nine of those years, serving as Editor of M-U-M.

And so, as is his habit, while it’s taken some time for Mr. Close to complete these two new books, they are unmistakably reflective of his furthering evolution as a magician, a father, and a man. As he explains in the introduction to Volume One of The Paradigm Shift:

I was no longer the person I was when I created the material in the Workers books or [Closely Guarded Secrets]. Performing those tricks now using the patter I created then seemed as if I was parroting someone else’s lines. It did not feel like a genuine expression of my life. To perform those routines again, I have to figure out what they mean to me now.

So, this book is different from those that have come before, because I’m different from the person who wrote those earlier books. The routines have not been performed a thousand times, and not every single detail has been discovered. But the construction of all of them is sound, and I currently perform them all. Many of the routines are more suitable for casual performance, but I don’t think that’s a bad thing. Most of you probably don’t work restaurants and cocktail parties; you perform for your friends and family. I think you’ll find these routines to be valuable additions to your repertoire for those situations.

While it may reflect the limited standards and expectations of the conjuring literature, I find these paragraphs to be remarkable, and invaluable. If art is a means of self-expression, and if magic is indeed an art (which I believe it to be, even if much of it is bad art), such writings should not be unusual in the tradition of our literature. And yet, they are. All the more reason then to value these works, before we even get to the explicitly conjuring content.

But now that we are there, the conjuring content is rich, dense, and engrossing. Indeed, there is so much of it that I will only gloss over much of the specific contents, because while Michael Close is my kind of magician – steeped in knowledge, perspective, taste, and skills – more importantly for readers, I would propose, is that these are my kind of magic books, and should be yours: filled to the brim with theory, technique, effects, history, perspective, experience, and a distinctive creator’s voice. What more do you want between the virtual covers of a conjuring ebook?

But for those interested in the particulars, I shall try to provide a useful overview. First of all, these two volumes are really, in many ways, one volume broken into two parts, which are well worth the total asking price. There is very little reason to purchase only one volume of the set; the only conceivable basis would be the fact that the second volume contains somewhat more demanding techniques, and accompanying routines that require such techniques. Hence the second volume utilizes a number of routines that require the ability to execute repeat perfect faro shuffles with relative ease, and also routines that depend on the ability to perform the Pass effectively, including as a primary option, Mr. Close’s new “Paradigm Shift,” after which the two ebooks are titled.

Volume One is worth its asking price for the two early chapters, “A Tale of Two Systems” and “Repose, Chaos, and Action.” The first of these chapters discusses the 2011 bestseller, Thinking, Fast and Slow, written by Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics laureate Daniel Kahneman. This book, incorporating an eclectic mix of subjects including cognitive biases and other behavioral science, medicine, engineering, and the author’s research on “happiness,” has won accolades in multiple arenas, including by many within the arts. A core thesis of the book is the notion of two diverging modes of human brain function: “System 1” which is rapid, intuitive and emotionally driven; and “System 2,” which is slower and more analytical. Mr. Close writes:

I think it’s pretty easy to see how the concept of System 1 and System 2 apply to conjuring. System 2, the system that does logical analysis, is not really our friend. System 2 is going to take in as much information as possible in an attempt to deconstruct our little mysteries. System 2 is going to look for answers, and while it’s looking for answers it will be draining resources and fatiguing our spectators. As much as possible, we want System 2 to be out of the picture.

Mr. Close (and a number of other magicians I know) highly recommend Thinking, Fast and Slow, but he has gone further, by building on Kahneman’s two systems in order to create a unified theory of conjuring reflected in the chapter entitled, “Repose, Chaos, and Action.”

The attempt to create working theories in the arts in general, and magic in particular, is invariably a worthy attempt. The books within the conjuring literature that specialize or significantly contribute to this effort number probably less than two dozen, albeit that bits and pieces of useful theory can be found within the pages of many, many more magic books (most typically in the “introductions” to those books, as I wrote about in “Making Introductions” in Preserving Mystery). But it’s one thing to create a theory; it is quite another to create a useful theory, that provides genuine utilitarian value over time. Sam Sharpe created a useful theory when he posited the existence of six basic magical effects in his classic text, Neo-Magic. Dariel Fitzkee cited Sharpe’s work when he posited his own theory of 19 basic effects in his classic theory text, The Trick Brain. In my own estimation, only one of these men created a truly useful theory, and it wasn’t Mr. Fitzkee.

Dai Vernon, Tommy Wonder, Juan Tamariz, and Arturo de Ascanio, among others, constructed useful theory models that have already outlived their creators. In his chapter, “Repose, Chaos, and Action,” Mr. Close contributes another invaluable tool that I believe serious students will be applying to their work – and thereby improving their work – for a very long time to come. What’s more, by way of example, Mr. Close explores and exemplifies this theory throughout the pages of these two volumes, and in this case, creates a marvelous dynamic that renders the material ever more useful beyond the limits of whether or not you actually put any of these tricks to use in your own repertoire. Much like The Books of Wonder, the act of studying the tricks is inseparable from the act of studying it, and thereby gaining insight, into the value and applicability of the theory.

Like most good theorists, part of what Mr. Close is doing here is naming something that some magicians have been using for a long time, even predating Mr. Close’s presence on the planet. But naming such principles is a key part of gaining understanding and command of them. Arturo de Ascanio did not actually invent the notion of “in transit actions,” because magicians had been using the fundamental principle for centuries, every time they successfully executed a Top Change. But Mr. Ascanio carried all of magic a theoretical leap forward when he identified and named the phenomenon, thus rendering it more readily understandable, accessible, and ultimately useable, but future generations. (Thanks, Arturo. We are grateful to you.)

I don’t think I’m giving away too many secrets if I quote directly from Mr. Close’s initial definitions here. And so:

Repose simply means that whatever prop you use is at rest: the cards are squared and sitting on the table; the deck is held in your hand, which is held below frame or by your side; coins are loosely stacked on your open palm or on the table. Repose gives System 2 the opportunity to evaluate a situation and sign off on it. Repose implies fairness. …

Chaos means that whatever prop you’re using is in a state of disarray or disorganization. Instead of the cards being squared up on the table, they are roughly ribbon-spread or they have been cut into many packets. If the cards are in your hand, they are not squared neatly. Coins are scattered or unsquared in your hand. Chaos kicks Repose up a notch; with Chaos we have the likelihood of achieving conviction. With Chaos, System 2 is convinced that everything is fair and nothing sneaky is about to happen. System 2 signs off with conviction, which is a powerful position for the magician.

Action refers to the procedure that accomplishes some secret methodological subterfuge: a card is going to be forced, a card is going to be controlled, a card is going to be palmed, the deck will be false shuffled, a coin is going to be palmed, a coin is going to be false transferred. When we perform an Action, we need System 2 observant but not on high alert. We want the outward appearance of the Action to register with System 2 but not have the Action set off any alarms. Understanding this is a key to more powerful magic.

So, there you have it, the guts of Michael Close’s Theory of Repose, Chaos and Action. His initial example concerns an analysis of how best to get into the Classic Force, and what’s wrong with cutting the deck as the way to do it. But this is simply the first of many examples that students will be able to study throughout the ensuing pages of these two substantial volumes.

Volume One then continues with seven substantial segments on technical tools that exemplify Mr. Close’s theories. These chapters describe in detail fundamental techniques that many students may already be familiar with, but whose execution (and theoretical understanding) will likely be greatly improved by studying Mr. Close’s analysis and instruction. These segments include work on the Cross-Cut Force (and yes, if you’ve always sneered at this technique, as I have, you might just use Mr. Close’s improved version, dubbed The Chaotic Cross-Cut Force); A Running Cut Combination; The Slip-Shoddier Shuffle; The Shoddy Rosetta Shuffle; A Touch on the Bobby Bernard False Cut; In Praise of the Lift Shuffle; and Give Me A Break, this last being a lengthy section drilling down on the break, a technique that Harry Riser considered the single most important sleight in all of card magic. If you don’t know all of these methods, you will become a far better magician by studying Mr. Close’s own close analysis and instruction. If you do know some or even all of these methods – you will become a far better magician by studying Mr. Close’s own close analysis and instruction. And remember that in both volumes, all of these sleights and techniques contain links to instructional videos demonstrating them, generally in both slow form and real time execution. (For what its worth, my personal preference would be that all of these clips retain the same order of these two versions, and in fact that the real time demonstration precede the slower version, because in many cases I simply want to see the proper execution as I’m reading the book, and will return to the slower version later when actually studying the sleight.) In Closely Guarded Secrets these clips were embedded within the ebook; since the current ebook formats that these new books are produced with will not function in that manner, the clips are privately posted on YouTube.

The book then delves into a section of 17 tricks, routines, and additional techniques, including a segment of six items (several card routines, a false shuffle, and a sort of Monte routine using rubber cubes) by Bob Farmer, previously published in the pages of M-U-M, which Mr. Close has noodled with and improved with his own touches and ideas. All of these tricks are potentially useful, and can be accomplished with moderately intermediate conjuring skills.

The first of these routines is “A Better Jacks or Better,” which comprises a number of fixes that the author has applied to a Darwin Ortiz routine entitled “Jacks or Better” from Darwin Ortiz at the Card Table. (In turn, the Ortiz routine is based upon Ron Ferris’s “Royal Aces” from Expert Card Mysteries by Alton Sharpe.) The Ortiz routine was originally presented as an example of extreme skill, namely the ability to progressively deal fifths, fourths, thirds, and seconds, and years ago I used the routine in that context. Mr. Close is not comfortable with this because he does not perform in the context of being a gambling expert, and as well, the trick contains an undeniable flaw, namely its reliance on the Braue Addition which, to quote Mr. Close, “… is one of the worst moves in card magic.”

Thus the author presents his reworking of the routine, addressing these issues of both method and presentation. In the final analysis, he admits that he had taken …

‘… a move that lasts ten seconds and replaced it with an entire trick that takes three or four minutes. Does that make sense? Does it make the trick better?’ I think it does. For me, it makes perfect sense; for you, my solution might not be the answer. There is no absolute answer, because at this point we are talking about aesthetics – the solution that fits depends on intent, experience, and your definition of magic. You must decide how you want your magic to look.

For many magicians, acquiring (or developing) an aesthetic sense comes from spending time with a mentor. I don’t think this sense is acquired by being taught; instead, the lessons are absorbed by observing the choices the mentor makes – what effects are performed, what sleights are incorporated, what methodological approaches are used. At the time I met Harry Riser, I had been studying magic for almost fifteen years. I was a sponge; I read everything I could get my hands on. My choice of effects was not based on any particular criteria; if I liked it, I worked on and performed it. I had no vision of how I wanted my magic to appear.

What turned my head around when I watched Harry work was he never used many of the sleights I used all the time: for example, the Braue addition and the Braue reverse. The way he did magic seemed a lot cleaner than the way I did magic; he didn’t leave any clues. When he finished performing, the reaction was, ‘But he didn’t do anything.’

This taught me that part of the creative process was editing. One approach may lead to the sensation of seeing real magic. Another may lead to the impression you’ve just watched a guy fiddling with a deck of cards.

I have included this lengthy quotation (and others) in order to try to communicate what I consider to be the greatest strengths of this deeply substantial work. Let’s assume the tricks are good, because they are. Let’s assume the presentations are clever, because they are. Let’s assume the methods are sound, because they are. But there are enough books with good tricks, good presentations, and good methods (albeit, maybe not enough, considering the piles of books that lack all of the above). But those paragraphs quoted above are consistent with my own long experience in magic, and help to explain why it takes such a damnably, excruciatingly long time to become a good magician. Today, with access to video and the Internet, sleights are in many ways the easiest thing to learn, even though that is a recent phenomenon. Tricks are easy to access as well. But learning how to create an experience of magic, learning to create a personal and artistic definition of magic (as Mr. Close importantly discusses at the start of this volume), learning how to express oneself through the medium of magic, and perhaps most challengingly, learning to acquire a sense of taste – these are tasks that require time, study, effort, and experience, and few indeed are the books that can genuinely contribute, in useful and constructive fashion, to these pursuits. The Paradigm Shift is one – actually two – of such books.

Perhaps I should mention that this routine also contains the following sentence: “The Encyclopedia of Card Tricks is card magic’s version of the witness protection program.” True to Mr. Close’s record, this was not the only laugh-out-loud moment I experienced in reading these books.

And finally, on the closing page of Volume One, the author comments, “Beauty lies in the attention to details; the finding and “fixing” of all the details, while a painstaking and sometimes frustrating journey, can be a source of great joy and satisfaction.”

And with that, we proceed to Volume Two.

Volume Two, as mentioned, contains a significant amount of material that relies on the use of the Faro Shuffle. Mr. Close’s Mentor, Harry Riser, was among the very first American magicians to explore and utilize the faro when virtually no one did the sleight, and so Mr. Close has a long history with the technique. Indeed, in 2001 he wrote a small pamphlet entitled Learn the In-The-Hands Faro Shuffle, which he has just reissued as a newly formatted and revised ebook, and for $25 is the best resource I know for learning this essential technique in the performance of sophisticated card magic. Like Mr. Close, I too first learned the faro shuffle in my teens from Close-up Card Magic by Harry Lorayne. I have done the faro the same way every since – from the top of the pack, down – but Mr. Close, in his youth, first witnessing Harry Riser executing the shuffle from the bottom up, revised his technique, and this useful and consistent method is what he so effectively teaches in this invaluable little manuscript. If you learn the faro from its instructive pages – and with the requisite practice, you most certainly will – the price will repay itself in value throughout the entirety of your life as a magician.

In Volume Two of The Paradigm Shift, Mr. Close provides superb instruction in several extremely practical and valuable utilitarian aspects of the Faro Shuffle, including an explanation of Homer Liwag’s False Faro, and its use, as applied by the author, as a False Faro Placement in applications from the Classic Force to the Open Index principle in memorized deck work. If you do a faro shuffle, and especially if you also do memdeck work, I can all but guarantee you will put some of these ideas to regular use in your work.

Several faro-based tricks then follow, including “The Way of the Duck,” a trick whose method is based on the fact that eight consecutive out faros will return the deck to its original order. If you can do the requisite faros (you only have to do five in front of the audience), the good news is that the trick is accompanied by a drily hilarious presentation. Yup – hard to believe, I know, but it’s true.

Moving on to the memorized deck, Michael Close was an early thought leader and influencer in the popularity of the memorized deck in the United States, and specifically the popularizing of the Simon Aronson stack. It may already be difficult for magicians to imagine this, but it was not so long ago, throughout the 1990s in fact, that Mr. Close was routinely devastating magicians in sessions and at conventions – a time when the Nine of Diamonds was just another card to most practicing magicians. Indeed, Mr. Close was responsible for my own deep dive into the memdeck, about nine years after his own start, a couple of years after I read his seminal essay, “Jazzin,” in Workers Volume Five.

In The Paradigm Shift Volume Two, Mr. Close begins with a brief overview of the past few years of publications of memdeck magic, highlighting what he regards as some good books and good tricks (assessments with which I heartily agree) that are worthy of every student’s avid pursuit. He then describes in detail a routine entitled “Card Control by the Numbers,” which as the author recounts, he performed at the “Stack Clinic” intensive seminar I organized and produced in Las Vegas in 2004, at which Mr. Close served as my co-presenter (along with Eric Mead as guest lecturer). At that gathering, following my performance of Juan Tamariz’s “Three Little Peeks” (which is called “Card Control” in Mnemonica), Mr. Close performed “Card Control by the Numbers,” which it is fair to say, as he speculates in Volume Two, fooled most every attendee present. (I also witnessed Mr. Close performing this routine at a lecture on memorized deck work that we co-presented at the 2016 31North conference in Toronto.) If you are capable of performing this routine – an impossible revelation of three selected cards under supremely fair conditions – you will thoroughly fool just about any human who witnesses it. Period.

Although this is an expert’s memorized deck routine, Mr. Close then provides a series of useful drills that will help you become an expert (and will likely improve even most experienced memdeck user’s mastery). I highly recommend these practice drills to any memdeck student, even those with longtime experience.

There are more than a dozen additional tricks and routines in this volume, along with several explorations of methods and techniques, which tallies up to a meaty and substantial 175 pages of thought provoking and enlightening material. This is not a book to casually glance at now and again or speed through to try to pick out just a move or trick that you like (albeit you could). This is a book that is worthy of your time and consideration that, like all good books, will reap rewards commensurate with the effort invested.

I enjoyed reading “How Did I Screw That Up?”, a deceptive routine with an even more clever presentation. I spent some time with the technical chapters describing Mr. Close’s work on Aaron Fisher’s superb Gravity Half Pass from his 2002 book, Paper Engine. I also took some time studying Mr. Close’s original approach to the Classic Pass that he has dubbed The Paradigm Shift, a shift that will be particularly effective for secret repositionings of the cards (rather than as a direct means of card control), using a delicate combination of mechanics, timing, and misdirection, rendering the sleight invisible if properly executed.

I also read with interest Mr. Close’s theories about “Who Has the Power?,” which discuss strategies for reducing the unpleasant dissonance that many people experience when faced with the impossibilities of conjuring and magic. This is as good a place as any to acknowledge that while I rarely disagree with Mr. Close’s fundamental theories about what makes for good magic – in terms of effects, methods, and presentations – my personal tastes and style often vary from his own. This is inevitable, and as I mentioned in my comments about the Workers series, should be considered a feature, not a bug. I love reading Mr. Close’s work, because it invariably helps me to think usefully about my own. I love watching him perform, because he’s a distinctly entertaining and mystifying magician. But in all these years I have only rarely adopted any of his routines, and have never adopted any of his presentations, not because they’re not marvelous, but because our personal tastes differ, and our performing styles and characters differ even more so.

And so while I completely agree with Mr. Close’s theories about the presentational value of placing the magical power of a magician’s performance in the spectator’s hands – as a way to reduce the spectator’s dissonance in the face of the frustrations of magic – I have rarely found this particular dodge an effective and comfortable solution for myself. Theoreticians like Whit “Pop” Hayden, Bill Nagler (whom Mr. Close references), and Gene Gloye (in his useful 1978 book, Theatrical Magic), among others, have discussed why the claim that “it’s fun to be fooled” often departs from the reality of many audience members. Mr. Close discusses Mr. Nagler’s theories on how to address this issue; Mr. Gloye, a child psychologist and performer of children’s magic, provides five such strategies, to wit:

- Release through laughter

- Identification with performer

- Insight and understanding

- Experience of awe or wonder

- Displacement

And Mr. Hayden, acknowledging the dissonance that magic triggers in many, if not most, people’s minds, opines that, “The sword of magic is hidden in the cloak of theater.”

I would suggest that every successful magician is incorporating some version of these strategies in order to reduce the spectator’s dissonance and make the experience of magic one in which it seems that “it’s fun to be fooled.” But even if one actually believes it’s fun to be fooled – and based on my experience, I do not – one is likely utilizing these strategies, consciously or deliberately or not, in order to obtain that positive outcome.

I take this brief theoretical detour because while I think that every effective magician must be using one or more of these strategies (along with others that include character and personal charm) in order to render powerful magic palatable to the audience (and if the magic is not powerful, that itself is a strategy, albeit an all too common yet undesirable one in my estimation), but it is unlikely that every magician would utilize all of these strategies, because not every strategy is suitable to every individual’s character, or vision of magic. And hence, while I found Mr. Close’s discussion of “Who has the power?” to be thought provoking and enlightening, I probably won’t be using his favored strategy for solving the problem that many people do not find it fun to be fooled. My point is not by way of criticism but rather about differentiations in personal style and approach, to wit: my personal choices may differ, but the author’s discussion remains invaluable.

To return to the book, Mr. Close then introduces the final segment with a commentary entitled “My Favorite Things,” which comprise the volume’s six concluding routines. Every one of these routines is a worthy entry, and while one of them as, as the author describes it, less than “a trifle” and more of a “bon mots,” the rest are blockbuster routines. “The Atheist Card Trick” is a surprising fooler that, in the words of the author, represents his “… best attempt to create an effect that offers a personal worldview and intellectual content.” You don’t have to use his presentation or embrace his rationalist worldview, but the piece serves as a fine example of how to invest oneself in one’s material – and that is, ultimately, the artist’s job.

In “The IKEA Card Trick,” Michael Close, as middle-aged father and family man, takes a universal experience – the frustration (and worse) that contemporary couples can experience when trying to collaboratively assemble a piece of IKEA furniture – and turns it into an entertaining card trick. Based on a genuine but somehow underappreciated classic, namely Dai Vernon’s “Vernon’s Variant,” Mr. Close manages to turn the plot on its head and thereby escape the “spectator as loser” element that repeats throughout the routine. This routine is so good that the author understandably hopes that “you’ll just forget that you ever read it.”

“The Trick That Fooled Houdini and His Whole Fricking Family” is, in Mr. Close’s estimation, “…one of the best routines I have ever created,” and I cannot help but agree. Were I to learn one routine out of these two new books, this would be it – a seamless blend of simplicity, mystery, and history, which charms the hell out of me simply in the reading of it.

In the final page of The Paradigm Shift, Volume Two, Michael Close offers:

I like a book that is both dense and deep. I get great joy from returning to a book I haven’t read in years and discovering information I missed the first (or second or third or fourth) time I read it. The book, of course, hasn’t changed; I have changed. We receive and absorb the information we’re ready to receive, and this depends on our experience and our knowledge. An old adage (probably of Theosophical origin) states, ‘When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.’ A great book is a patient teacher that waits for you until you are ready to accept the information that has been in front of you all along.

The Paradigm Shift Volumes One and Two, by Michael Close, are – by this measure, among others – indeed great books.

—♦—

The Paradigm Shift, Volume One, The Paradigm Shift, Volume Two by Michael Close ebooks; 194 and 175 pages, respectively; illustrated with color photographs; includes links to instructional video clips; 2018; Price: $39.95 each or $69.95 for the set of two volumes. Available online.

AND...

Here are three performances by Michael Close that reflect three periods of his work, and three sets of writings discussed in the review.

Michael Close - Potholes

“The Pothole Trick” is one of the most enduring and popular of the many routines contained in the Workers series, and remains a favorite of its creator.

Mike Close Magnetized Cards

This is Michael Close’s original presentation – distinctly reflecting his performance style – of Gary Plants’ method for the classic Magnetized Cards, and was included in Closely Guarded Secrets.

Michael Close - The Atheist Card Trick

And here is a feature routine from The Paradigm Shift that is an excellent example of clever methodology, accompanied by an authentic personal presentation (a video that was originally posted as part of the “Openly Secular” social campaign.

LAST BUT NOT LEAST…

Michael Close is a skilled teller and enthusiastic collector of jokes. This collection of jokes, along with the author’s related personal anecdotes, is the best joke collection I know of, because these are the real jokes that real joke tellers tell. I’ve heard some of these jokes out of the mouths of some of the world’s greatest professional comics who, when offstage among their friends and peers, don’t do their own stage “material” at one another, but rather, tell jokes like these. This book is a hidden little jewel in the world of sociable laugh-getting. The link below offers Mr. Close’s audiobook version; on the same page you will find links to print and ebook editions as well.

That Reminds Me: Finding the Funny in a Serious World by Michael Close

SEE LYONS DEN INDEX