Submitted by Jamy Ian Swiss on

Looking back, I realize more and more these days that growing up in magic at the original Tannen’s Magic shop in Manhattan was a rare gift and opportunity. Tannen’s would, it turns out, play an overwhelmingly powerful role in my development in magic, and my eventual pursuit of magic as a career—an influence and opportunity that, as a boy, I could not fully recognize at the time. But today I see ever more clearly the fact that Tannen’s is a constant presence in my memory—the very foundation of my learning and growing throughout a lifetime in this art.

I’ve often written about Lou Tannen, my first sleight-of-hand mentor—and I have done so at length in a memoir piece entitled “Real Secrets” in my book Shattering Illusions. And in a quick search here in the Lyons Den, there are no less than twenty-five pieces—mostly from Take Two—that come up wherein I’ve mentioned Tannen’s Magic, most of which reference my attendance at the annual Tannen’s Jubilee convention, where I saw countless great acts perform and lecture, both in close-up and on the stage.

On many a Saturday, beginning when I was about 11, I would make the long subway trek from Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn to Times Square, head to the Wurlitzer Building on 42nd Street across from Bryant Park, and take the little weekend freight elevator up to the 12th floor where, finally, the door would open and take me into another world—a world full of color and wonder beyond imagination and compare. As an inordinately shy and only child, it took all my courage to step up to the counter and ask a question of Lou, or one of the demonstrators, before deciding on my excruciatingly-deliberated purchase, which typically only totalled a few dollars. But then came the profound moment when Lou would take me aside, away from the crowd, and bestow the secret upon me—the highlight, and privilege, of the venture.

The rest of the time, I was far too shy to make friends, or to ask questions of the experts gathered there, who so intimidated me. But still I was compelled to stick around, for hours at a time, to try and see as much as I could, when I was permitted (and often I wasn’t), to see something marvelous in the hands of a noteworthy bystander. And of course, I could also return to the counter, over and over again, to watch the endless demonstrations of tricks from the bursting showcases. It was said that Lou could demonstrate every trick in the store, and I don’t think there was much hyperbole in that claim.

At three o’clock, when the store closed on Saturdays, most of the crowd would head over to the nearby Governor’s Cafeteria. The group would take over a bunch of tables in the back in order to session well into the afternoon until dinnertime, or beyond. In those early years I wasn’t a part of that; I was neither bold enough, nor really old enough, to be allowed to stay behind.

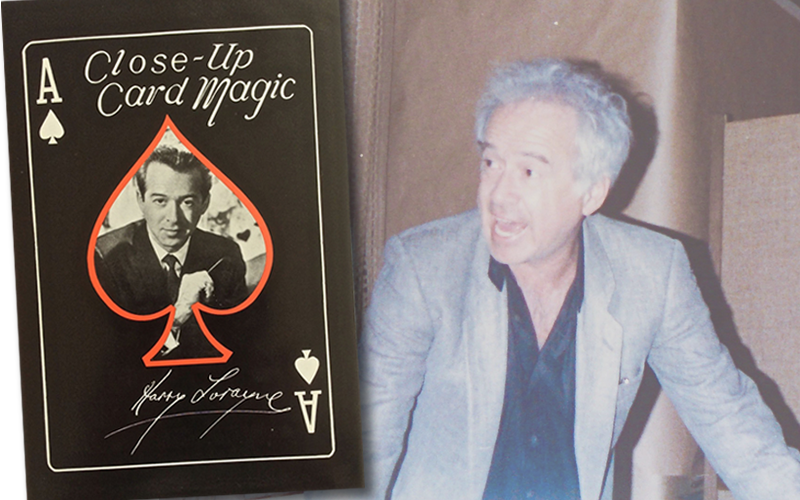

It wasn’t until I was 17 that I developed a serious interest in card magic, and that’s when I began to hang around the cafeteria. I was still very much an introvert, and was never really an insider there—but I got to see a lot of great magic. This was also the period when I made the three discoveries that every close-up magician of my era names when asked about origins: The Royal Road to Card Magic by Jean Hugard and Frederick Braue; Close-up Card Magic by Harry Lorayne; and seeing Don Alan on The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson and on The Ed Sullivan Show. And thus was spawned a generation, or two, of close-up and card magicians. Ask any one of us: that is our holy trinity; that is our collective origin story.

I hope my non-magician readers will indulge me as I, in this particular Take Two, step a little further into detail that may be of greater familiarity to the magicians among us. I actually got Royal Road in my early adolescence and learned the fundamental techniques and several of the basic tricks. I was also doing general sleight-of-hand close-up magic and had a steady interest in coin magic. Back then, Tannen’s was also a publisher, and rather than pulping damaged and misprinted books, Lou would offer them at a discount price to kids like me. My first five volumes of The Tarbell Course In Magic are all somehow damaged, misprinted, or missing pages—and I’m grateful for getting to study that material when I was so young. One day Lou took me in the back where he kept all the damaged books—ever a wondrous experience to be permitted to step behind the counter!—and offered me a misprinted copy of Close-up Card Magic.

That damaged copy of Harry Lorayne’s now legendary first book was, as the saying goes, a game changer for me. I didn’t understand all that much of it at first, but a couple of years later, a friend taught me the Vernon Double Undercut and got me working on Lorayne’s instructions for the Faro Shuffle. From there on, I was truly off and running down the path toward serious artistic card magic.

Lorayne was a constant presence around Tannen’s, and one of the chief holders-of-court at the Saturday afternoon cafeteria gatherings. Eventually I would come to know his lecture so well that I felt like I could have probably duplicated it if I had to. I can’t even guess how many times I saw him perform and explain HaLo Aces!

Lorayne was a national celebrity as both a television performer and as a best-selling author—but that had nothing to do with card tricks. For all the books and journals he would eventually produce about card and close-up magic, he mostly kept that side of his life from the public. Why? Because Harry was known as a “memory expert.” His 1974 book The Memory Book was a New York Times bestseller, and one of several books about memory he would write over the course of his career. So while I saw him doing card magic at the magic shop and at the cafeteria, doing lectures at Tannen’s Jubilee, and performing on stage at the Jubilee as well, when I watched him on television—typically on The Tonight Show, where he appeared no less than twenty-four times—Lorayne would perform amazing feats of memory, not magic. In Harry's signature memory routine on The Tonight Show, Carson would first set the scene: he would explain that before the show, Harry had greeted and shaken the hand of every audience member, learning each person’s name as the crowd entered the theater. Then, during the show, Lorayne would ask the entire audience to stand, whereupon he would call off each and every person's name, with each one sitting down as his or her name was called, until the entire audience was seated. (There was always one name in the middle where Harry would feign having difficulty with, only to successfully name that person as a climax to the routine.)

The combination of super-human memory demonstrations with his New York-accented machine-gun commentary and outsized Energizer-Bunny performing persona rendered Lorayne as an unforgettable character. But because his memory mastery was real—based on timeless principles of mnemonics honed to a fabulous degree—Harry didn’t want any mention made in those settings about his passion for magic, because he didn’t want people to think that the memory stunts were tricks.

Meanwhile, in my late teens and early twenties, there were two men on the New York magic scene who powerfully demonstrated to me that it was possible to thoroughly entertain an audience with little more than a pack of cards and a pair of hands: Harry Lorayne and Frank Garcia. The two were actually bitter rivals, but that’s beside the point for this story. I admired and was inspired by both of them, and I learned from both of them—I learned a lot. I studied their books, I attended their lectures, I asked them questions at the magic shop. Their influence remains palpable in my work to this very day.

By my early twenties I was thoroughly obsessed with card magic. As an amateur performer, I followed—or more accurately, I anticipated—the advice that Eugene Burger would codify in his writings a decade later. But this was before I, or anyone else, had heard of Eugene, and before he ever set pen to paper to write about about magic. During these formative years, I concentrated on mastering a small repertoire of material, accompanied by original scripts, written down and well-rehearsed, which I would put to use when called upon to perform at social gatherings. While I was constantly working on new things, that core repertoire, if I performed all of it, amounted to, perhaps, 25 minutes, which included a strong closer and an optional encore piece. I always had a deck of cards with me in case the opportunity arose. I could vary the set with other material like coin magic, or some other close-up prop I might have put in my pocket, but the card set became the core of my amateur performance repertoire. And of that set, several pieces were drawn directly from Lorayne’s Close-up Card Magic, and from several of his subsequent works.

So recently, when a student of mine happened upon a number of Lorayne publications and expressed an interest in them, I recommended Close-up Card Magic, along with a few other early titles. And I found myself wondering what it would be like to study that material now, more than half a century after it was originally published—and half a century after I had studied and been shaped by it. (I’ll have to update the credits for my protégé: back in the day, Lorayne’s approach to crediting was often imprecise and sometimes downright lacking. But that was a different time; a time before the literature became properly obsessed with tracking the credit record.)

There is no doubt in my mind that Lorayne’s clear and personable prose is as effective an instructional guide as it ever was. And what about all those great tricks I learned, loved and performed, that served me so well for so many years? Tricks like Lorayne’s Poker Deal, The Lazy Man’s Card Trick, Foursome, The Magicians versus Gambler, the Color-Changing Deck, The Card Sharp and the Four Gamblers? That’s not even mentioning the utility sleights and techniques I found scattered amid his first eight or nine magic books—books that I pored over, committed to memory, filled with routines that I polished and performed. What of Stabbed in the Pack, along with the correspondence in The Best of Benzais by Johnny Benzais, which would eventually inspire my own routine, Stabbed in the Sandwich, a feature of my Magic Bar days in the Eighties, and indeed, in my current magic lecture today?

And so, I dropped Harry Lorayne’s name into a YouTube search and sure enough, a number of clips came up, many from a set of instructional videos he made for magicians a few decades ago. The sudden sense of time shifting was overwhelming as I watched tricks and routines that I haven’t thought about in years, or even decades, but which still occupied a tremendous space in my head—and remain present, in some way or another, in my work and my life in magic.

There’s so much more to the story of Harry Lorayne—how he grew up as a poor Jewish kid on the Lower East Side, how “He stole empty milk bottles from in front of apartments in the tenement in which he lived so that he could collect the $.02 deposit on them and be able to afford a deck of cards.” I heard that story out of Harry’s mouth countless times, but that sentence is drawn directly from his carefully control-freakish, curated Wikipedia page, where you can see lists of his books, his television appearances, his memory work, and much more. A lightning rod for controversy throughout his life, searching online magic forums for his name, rushing into battle over the smallest perceived slight, and thus, perhaps, less appreciated by a younger generation that wasn't around to witness, firsthand, those undeniable glory days as an ever-present influence.

But I’m here just to talk about the card tricks. And, I guess, to also say: Thanks, Harry.

The Ambitious Card Routine

The four routines I’ve selected here are all drawn from Harry Lorayne's Best Ever Collection, originally produced on VHS format. You know the drill, but please—set aside the smart phone, expand the browser to the max, and turn up the volume, and get ready to enjoy some of the classic card magic of the truly inimitable Harry Lorayne.

Here is one of the pivotal, foundational plots in close-up card magic. Most magicians have such a routine in their repertoire (some of which I’ve posted in previous Take Two’s, including in the previous installment about Pat Page). Because of the nature of the methods and techniques applicable to this plot, magicians often continue to study and update their versions of this trick, as their skill and technical repertoire advance.

In my case, I began by studying two notable routines—one by Dai Vernon, from the original Stars of Magic (yet another seminal work published and sold to me by Lou Tannen, and one of the most important works of close-up sleight-of-hand magic of the 20th century); and the other being that of Harry Lorayne, as described in Close-up Card Magic.

I varied and honed my routine well into my late twenties, and it became the cornerstone of my work as a Magic Bartender in the Eighties. And it remains a staple of my repertoire, ever-present in my shows in the Close-up Gallery at the Magic Castle. When curating videos for this post, I watched this clip and was seized by the realization that three phases of my routine had evolved from my close study of Lorayne’s version from some fifty years ago. I love the bravura feat he starts this off with, one I saw him do many times at lectures and performances.

Lorayne's Poker Deal

This was probably the first gambling-themed routine I ever performed on a regular basis. It’s actually Lorayne’s original and engaging presentation of a collaborative creation of author, mathematics junkie, skeptic, amateur magician and all ‘round polymath Martin Gardner, along with the prolific card magic innovator, Ed Marlo. Indeed, elsewhere on YouTube you can find Lorayne’s alternate version, which is even closer to the Gardner/Marlo original. Credit where credit is due aside, in my youth I performed this exactly as Lorayne does here, virtually to the word.

Magician vs Gambler

As my pursuit of sleight-of-hand card magic progressed, so did my continuing study of Lorayne’s work. Eventually, the time came when I grew sufficiently determined to attempt this next routine—a story kind of “presentation” (what we, as magicians, say and how we frame a trick or routine) that also required some of the scariest sleight of hand I had ever attempted.

It went well the first time or two, and I developed an unwarranted sense of confidence—until I was challenged by a woman who caught me out. It was an utterly humiliating moment, the details of which are mostly lost to time, but the sensation of which is indelibly etched into my soul. For some, those moments are the deal-breakers—the ones that terrify you and send you running back to simpler tricks, or abandoning magic altogether for hobbies less risky to one’s psyche. Instead, I was motivated to improve, and I did. And this trick became a staple of my amateur repertoire for years. It brings back an ocean of memories as I watch Harry perform this.

Card Shark & Four Gamblers

Becoming an enthusiastic adopter of Lorayne’s story-telling scripts, by my early twenties I adopted this next routine. As I eventually realized, it is based on a classic routine of Dai Vernon’s entitled Cutting the Aces, from the aforementioned Stars of Magic. I significantly rewrote Lorayne’s script into my own lengthy narrative, and constructed it as a more serious, first-person tale. For many of my later amateur years, this became my dramatic, after the show, late-night extra, when the party had quieted down, and when I was asked to perform “just one more.”

When I became a professional and abandoned this routine, lacking the time or the inclination for such a lengthy and contrived story, I published the script in a set of my lecture notes called Theatrics. (Years later I discovered that Johnny Thompson and I had thought along similar lines in one element of our respective presentations, which Johnny used for his performances of Vernon’s original trick, in that we both added a switchblade at the key dramatic moment.)

HaLo Aces—at 90

There’s plenty more where this material came from. Lorayne, at 92, continues to reassemble and repackage much of his earlier work as well as adding newer versions and material, too. His latest book, And Finally!, proclaimed to be his last, is available here. But for old time’s sake, I’ve included this one last piece.

Here is Harry Lorayne two years ago, at age 90 (and assisted by the way, but none other than Paul Gertner), performing one of those signature pieces of his that I watched repeatedly, and studied obsessively, about a half a century ago … more or less—but who’s counting?

SEE TAKE TWO INDEX