Submitted by Jamy Ian Swiss on

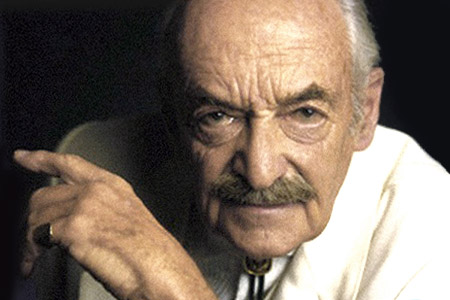

René Lavand

Take Two is, at its core, a course in art appreciation—specifically, the art of magic. I’m pleased that the series has interested not only magicians, but has also attracted an audience of non-magicians, who continue to comment favorably in the Facebook postings, as well as in many welcome emails to me and to lyonsden@magicana.com. And so I am particularly pleased this week for the non-magicians among us here, because I will get to introduce them to an artist they have likely never seen—even though he was one of the greatest performing artists I have ever encountered. His name was René Lavand.

René Lavand was born in Argentina in 1928, and became interested in magic at the age of six. At the age of nine, he lost his right hand as the result of a car accident. Rather than dissuading him from his pursuit of magic, it may have served to motivate and elevate his passion—a passion that he uncompromisingly pursued until his death at the age of 86 in 2015.

Lavand became an accomplished and eventually internationally revered sleight-of-hand artist, although he did not become a professional magician until he reached the age of 32, when he seized on several opportunities he found himself presented with, abandoned his day job, and devoted himself to a life in magic. From the time of his teens he had performed a silent manipulative stage act with billiard balls, with which he eventually found success, but did not entirely satisfy him artistically. His real passion was for close-up sleight-of-hand magic, with an emphasis on card magic. But since there was little in the way of literature about how to perform such magic with one hand, he set out to devise his own methods.

Yet there was nothing simple or technically minimal about the magic that interested him. Lavand was deeply engaged with the literature of close-up sleight-of-hand, as he was equally with the arts in general. Later in his life he proclaimed himself the ultimate autodidact, but at the same time, a passionate student who had “never met” his teachers, naming as influences an eclectic range of artists from Picasso to Stanislavski to Mae West.

The card magic he mastered was derived from the most sophisticated artists of his time, and when he eventually travelled to the United States his work was hailed by the likes of Slydini and Dai Vernonthen; he found himself similarly embraced in Spain by the likes of Arturo de Ascanio and Juan Tamariz. Eventually Lavand was to develop a style and character that was distinctly and profoundly his own.

I did not know him personally, although I was fortunate to attend a lecture in the late 1980s that was literally breathtaking. When I think of Lavand, the word that always comes to mind is gravitas. In his autobiography, Lavand writes about his father (who died when Lavand was only 18) emphasizing to his son the importance of dignity above all. Lavand took the lesson to heart, and dignity was an element deeply present in his work.

Lavand became a beloved public public figure in the Spanish-speaking world, from his native Argentina and across the Atlantic to Spain, and also appeared early in his career on The Ed Sullivan Show and on The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson. But he was also revered by magicians, even though relatively few got to see him perform in person. Magicians we astonished by two entirely different elements of his work. On the one hand, his technical abilities were astonishing to the point of disbelief; Lavand performed the most difficult sleight-of-hand invisibly and impeccably, utilizing techniques that most magicians would find challenging with two hands. Lavand recounts a story in the pages of his 1988 book, Slow Motion Magic, about presenting a lecture for a small group of magicians in Germany. After a time he detects that the students are growing increasingly frustrated and perhaps disheartened, no doubt because the more Lavand would explain the work, the more impossible it seemed to accomplish by mere mortals. And so he becomes distracted by the feeling in the room, loses track of his train of thought, and finally pauses to offer the group some consoling words, to wit: “Gentlemen, you know, this can be done with two hands, also!”

But on the other hand, magicians—especially the ones really paying attention, and able to take in the breadth of Lavand’s work above and beyond the incomprehensible technical mastery—also marveled at the power of his presentational style. Lavand was riveting—the audience found his demeanor, expressed in every gesture, in every carefully chosen word, utterly captivating. To me, he was the epitome of Eugene Burger’s dictum that first and foremost, you cannot expect your audience to take magic seriously unless you take it seriously yourself.

Lavand was a marvelous storyteller—another facet that magicians often speak of when they think of Lavand’s work—and yet he did not always rely on stories throughout his work, sometimes simply letting the magic speak for itself with the most minimal of verbal accompaniment. And for all his perceived seriousness, in his real work for the public he also knew how to get laughs. (Juan Tamariz once told me a hilariously ironic story about this very facet of Lavand’s work, a facet he was inclined to deny yet was inescapably present in his work.)

As to his one-handedness, through most of his career he ignored the fact in the course of performance, wanting the audience to forget that he was performing with one hand, or leaving them to wonder why. His performance was rich with persona, presence, and deeply mystifying magic, and he did not wish to impress people by featuring his condition. Late in his life, however, one particular performance piece departed from this operative premise, as you will soon see.

The challenge of art is to communicate an individual’s ideas and point of view through the restrictive and challenging confines of one's chosen medium. There may be no greater example of this in magic than in the work of René Lavand—who imbued every detail, every moment of his performances, with the richness of his passionate and artistic spirit—and you are about to find this out for yourself. I am deeply sorry that you will never get to see him in person, because as we know and I have often commented here, no recorded medium can do more than a fraction of justice to the experience of magic. But I also envy you, because for those who are first meeting this maestro now, you are about to experience something truly awe-inspiring, that you have never conceived of, and will never see the likes of again. Ladies and gentlemen, I present the maestro: Signor René Lavand.

You know the drill, but permit me to remind you. Please! Put aside the smart phone and commit to watching these performances uninterrupted and without distraction. Expand the browser. Turn up the sound. Give this great artist your undivided attention.

I’ve provided the correct title here for this routine, instead of the mistaken one on the YouTube posting, but this remarkable performance piece is quite possibly Lavand’s most famous among magicians. Based on one of the oldest plots in magic, Lavand’s version takes the plot far beyond any other known version, before or since. Please pay attention to this—it is in every sense of the word, a masterpiece.

René Lavand: The Three Breadcrumbs

Based on a classic card routine of Dai Vernon’s, Lavand’s one-handed approach renders the piece all the more amazing.

René Lavand: A Duel In The West

Although stripped of his trademark dramatic storytelling, Lavand’s presence still shines alongside Ed Sullivan in this historic appearance.

René Lavand: "Ases del Manco" (Ed Sullivan Show)

Finally, feel free to take a pause to refresh your concentration before returning for this eight-minute finale. Here you get the complete Lavand, in all his poetic grandeur. Eventually the magic in this piece comprises one of Lavand’s most famous routines, “I Can’t Do It Any Slower”—Lavand’s deliberate pace, inspiring the title of his first book, Slow Motion Magic, renders his magic impossibly clean and deeply amazing. But this particular version frames the piece within a self-constructed myth about his own life story that, uniquely in his work, acknowledges in its way the fact of his one-handedness.

René Lavand: Counterpoint Between Both Hands (with English Translation)

And an optional bonus

If you want to see more, this nicely produced clip showcases Lavand on UK television, graciously hosted by the most famous British magician of the time, Paul Daniels. Lavand performs two routines, The Gambler, and a more straightforward version of “I can’t do it any slower,” presented in the manner in which he typically performed it. (It doesn’t get any less amazing the second time.)

René Lavand on the Paul Daniels Christmas Show - 1987

SEE TAKE TWO INDEX