Submitted by Jamy Ian Swiss on

A Rave Of Reviews

Reviewed by Jamy Ian Swiss

In the past two years, I’ve reviewed about nineteen books here in the Lyons Den. Reviewing about one book a month has meant that a number of books have accumulated that I haven’t gotten to, for one reason or another. So with this almost end-of-year column, I thought I’d try and catch up by offering a handful of briefer-than-usual-but-better-than-nothing reviews. In every case it’s because I think these books are worthy of your attention, and not because I think any less of them than many of the works to which I’ve previously devoted more space.

And there is so much good magic to share, I'm breaking “A Rave of Reviews” into two parts, with this being the first, covering five titles.

Here we go...

Scripting Magic 2

By Pete McCabe

If I was pressed to pick a favorite book among this rave of reviews it would be this one, Scripting Magic 2. It’s Pete McCabe’s sequel to his 2009 book, Scripting Magic, to which I contributed a 10,000-plus-word essay about Eddie Fechter’s neo-classic quickie card trick, “I’ve Got A Surprise For You”.

McCabe is a schoolteacher and professional writer, and Scripting Magic became an instant hit. So much so, it has been out of print but in demand for a long time. Fortunately, Vanishing Inc. has reformatted it, and is re-releasing it in tandem with this sequel.

If you do magic—plain and simply, any kind of magic—both of these volumes not only belong in your library, but they also belong on the top of your reading list.

Everybody talks about scripting, but nobody writes much about it. Perhaps more to the point, virtually nobody wrote about scripting at all, particularly for close-up magic, until Eugene Burger burst on to the scene in 1982 with his debut booklet, Secrets and Mysteries for the Close-up Entertainer. Therein he wrote, “I have always personally favored a written script for every effect.” And thus, a revolution in thinking was born, and it echoed and was expanded upon throughout the ensuing decades of Eugene’s influential writings. Certainly, others have since taken up the call—Handsome Jack, etc. comes to mind as a significant example—but McCabe’s Scripting Magic is distinctive not only in that it devotes an entire volume to its eponymous subject, but it also does so in an exceptionally pragmatic manner. I’m not here to review that book, but suffice to say: I like it a lot.

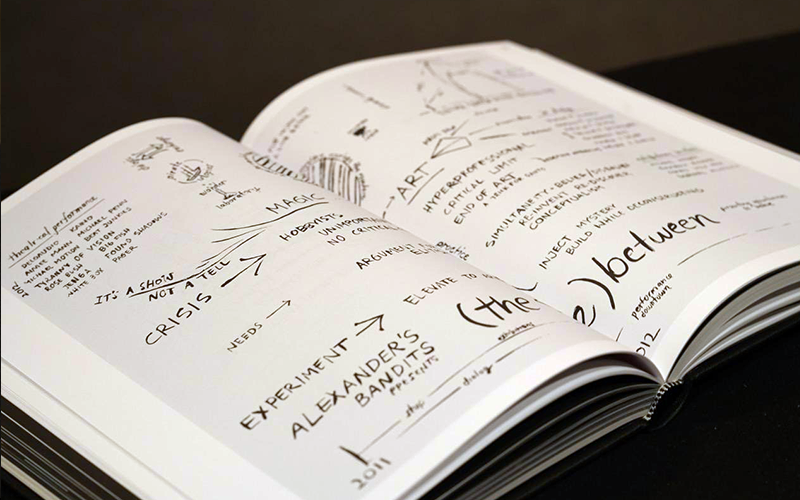

In the opening page of Scripting Magic 2, the author offers that while his previous volume “focuses on communicating information, and not as much on the work being done,” Volume 2 contains “fewer essays; things are arranged around creative exercises.”

And off we go!

The title page of Volume 2 states that the book contains “33 scripts, 9 exercises, 3 interviews, 93 illustrations and 1 flowchart to make you a better magician,” and that concluding claim is not hyperbole. I daresay that anyone who spends time with both of these excellent books will come away with genuine “deliverables” (apologies for a moment of horrible corporate speak; I’m back now) that will help any magician—from a beginning amateur to even an experienced professional—for years to come.

Now, I’ll be honest: I’m big on reading and thinking. I’m not big on doing “exercises” I find in books. That’s not much to my personal taste. I thoroughly enjoyed McCabe’s first book, as there was little attempt to reach across the page, grab me by the wrist, and set my pen to paper. But I’m not going to argue the intent, nor the claim that the author’s pedagogical focus in the second volume will doubtlessly be effective for many. If you’re not in the habit of actually doing the work, then what the author presents you with is a guided pathway toward, well … doing the work. Perhaps that’s the point.

I’ve been writing scripts since I was a teenager—long before I met Eugene Burger—and, at least one of those scripts, written when I was fifteen, eventually found a home in my professional work, decades later, and remains there today. But McCabe is a professional educator, and as such, he has carefully, and with obvious commitment and sincerity, created this book to encourage you in every conceivable way to get down to doing the work. You could not ask for a better guide.

Along the way he discusses subjects including the difference between plot and effect; character; confession; props; first lines; structure; connecting with the audience; and more. But this is not just highfalutin theorizing; rather, the book brims with practical examples, from McCabe’s own performing repertoire as well as from well-known contemporary professionals.

Many of my favorite chapters will be found among the the interviews and essays. A conversation between McCabe and Michael Weber about story—“Best Story Wins”—is a scintillating piece of work than should be read, chewed over, considered, read again, and thought about further.

John Lovick contributes an outstanding essay reprinted from Handsome Jack, etc., “Persona and Other Pieces of the Performance Puzzle.” Magician and professional screenplay story analyst Rubin Padilla offers “The Three-Eyed, Six-Legged Monster” guide to story and screenplay construction. And, he concludes this piece with a single, devastating paragraph about Harry Houdini that should be referred to anytime you hear or read a Houdini naysayer babbling on about how he “was just a good PR guy.”

By the way, if you’re averse to scripting, or even more so, perhaps, to the notion of considering acting as part of your skill set, McCabe puts forward a terrific and succinct thesis demonstrating that all magicians act, and indeed, that all magic requires acting. In other words: you're already doing it.

There are complete and polished performance pieces included throughout the book, and so you may well come away with something you can perform, right from its pages (albeit, one hopes, with your own script). One of my favorites is a delightful impromptu mental effect of McCabe’s devise, done with a small packet of M&Ms.

I will caution however that McCabe’s taste in methods leans toward minimal sleight-of-hand, and so there are routines here that depend on the PATEO Force and other such procedure-heavy methods that don’t particularly appeal to me. That said, many of the accompanying scripting examples, including Robert Neale’s highly regarded “Sole Survivor” routine, still serve as effective teaching examples, and of course, that is their primary purpose within the context of this volume.

One feature I should also compliment is that even in a book focused almost entirely on presentation, McCabe goes the extra mile when it comes to providing thorough crediting for every effect and method that he mentions. This sets an important example, by reminding us that crediting is an important part of every magician’s knowledge base. In fact, such knowledge is not only ethically and professionally responsible (and expected), but it is also fundamental as it helps to inform and enrich one’s own performances. (And under the heading of Nobody’s Perfect, the circle/triangle probability force, far from having been “invented about a week after Isosceles invented the triangle” [albeit that’s a nice joke] was in fact created, about 2,000 years after the compound Greek word “isosceles” was coined, by none other than Uri Geller [file this under the heading of “Giving the Devil his Due.”])

Difference in tastes aside—and in a book like this there are bound to be differences for every reader, and different differences at that—Scripting Magic and Scripting Magic 2 are outstanding tools that are designed to improve your magic, no matter what kind of magic you do, no matter where you stand on your personal path of artistic evolution.

I daresay there is not one book of tricks—much as I love good books of good tricks—that offers the potential of having nearly the beneficial impact on your work as a study of these two books almost certainly will. Between them, they offer more than nine hundred pages of thoughtful, tasteful, encouraging guidance. Do not let Pete McCabe’s hard work die on the shelf in vain. Get your hands on them, and get to work. McCabe writes in his closing pages that the goal of his first book “was to get more magicians” to write scripts. “The goal of [Volume 2] is to help you learn how to do it.” He’s done all he can possibly do to help you achieve that goal. Now, it’s your turn—to get to the doing.

Scripting Magic 2 by Pete McCabe. 6” x 9” clothbound hardcover with silver foil embossing; 455 pages; illustrated; 2017. Available from the publisher Vanishing Inc., $50.

The T.O.M. Epiphany

By Michael Close

Michael Close certainly needs no introduction to any serious, or even semi-serious, magic student and reader. It would be superfluous to repeat his credentials here; if you’d like some more background, check out my review of the two volumes of his latest substantial books, The Paradigm Shift.

Close is a busy and productive guy. Recently, he’s been producing live “webinars,” some of which are now available as downloads on his website, including presentations about memorized deck magic that I’m betting are invaluable investments for magicians either early on the path—such as “Demystifying the Memorized Deck”—and for those further along but wanting to go even further, there is “Memorized Deck Magic—Taking the Next Step.” You can find these products and much more, as well as subscribe to his newsletter, on his website.

Meanwhile, Close’s most recent publication is a small e-book entitled The T.O.M. Epiphany. T.O.M. stands for Three Operational Methods, a theory that Close discovered forty years ago in an entry by Stewart James in Howards Lyons’ journal, Ibidem. The epiphany part refers to Close’s own, experienced more recently when he came to an insight about how to practically apply this principle in analyzing one’s own magic routines, leading to better and more deceptive methods, presentations, and overall routine construction. As the author states in his introduction,

…“Three Operational Methods” … is not a theoretical problem or a lofty aesthetical one. It is a nuts-and-bolts problem. The Three Operational Methods (T.O.M. for short) put a restrictive grip on your ability to create new magic; for astute, analytical spectators, T.O.M. provides a logical pathway for unraveling the mysteries we present. Frustratingly, the Three Operational Methods are hardwired into human beings; we cannot beat them. However, after many years of thought, I have formalized strategies to do an end-run around them.

It’s worth copying the author’s own promotional description of the e-book here:

In The T.O.M. Epiphany you will learn strategies for accomplishing this. This is not a theoretical or aesthetical discussion. This is nuts-and-bolts information I have applied to simple and more advanced effects. You will immediately be able to appreciate the effectiveness of this approach. …it will change the way you think about the routines you already perform. The great news is that these changes will not require greater physical dexterity; this means the information is of benefit to magicians of all skill level.

I believe that the main reason that Spain has replaced the United States as the capital country of innovative close-up magic in the past generation is not only because of the quality of its mentors—first and foremost, Juan Tamariz—but that America lost a generation of future mentors due to early deaths, notably with the likes of Michael Skinner, Derek Dingle, Larry Jennings, and Bruce Cervon. This gap has contributed to a significant stagnating of creativity and innovation in American close-up magic, a vacuum filled by download and YouTube marketing (a phenomenon decried in every part of the sophisticated world magic community, including in Spain).

But another generation is now coming to the age of mentorship; artists like John Carney and Michael Close, among others. These individuals are producing invaluable instructional guidance and providing inspiration that stands heads and shoulders above the glut of self-styled wonders with inflated egos and tiny genitals ever-ready, in Kanye West fashion, to declare themselves the heroes of their own narrations, and the suckers latching onto such nutrient-lacking teats flowing from the glands of the magic-is-dead lot.

Close is a complete package when it comes to being a theoretician and influential mentor. He is not only a veteran performer, the author of some monumentally important works like the Workers series, but he is also actively committed to effectively communicating his ideas and to providing useful instruction to his students. In that interest, he not only produces the aforementioned webinars, but for years he, in collaboration with his partner Lisa Moore-Close, has been an innovator in producing multimedia e-books that seamlessly incorporate video instruction. This feature is utilized throughout the e-book at hand, which in addition to the video, also contains crisp color photography for illustration.

Beyond explaining the background to The T.O.M. Epiphany, as well as the principle itself, the author provides “updated and refined handlings” for six of his previously published routines, along with a new two-card routine that, if you are capable of executing the requisite sleight-of-hand, you will be able to use immediately. And in his revisiting of his well-known “Pothole Trick,” the author provides an anecdote, and an audio recording, that really made me laugh.

There is no easy way to summarize the T.O.M. theory and Close’s thinking about it, so if I appear to be playing coy, I assure you that is not my intention. I can say, however, that some of the issues he discusses as tools to be put to use in his analysis are elements of clarity, scripting, and lying. Others have invoked all of these principles in the literature and theories of magic—there are automatic associations of certain names that will come to you even as you see those words on the screen here—but they all apply to Close’s thoughts about beating the limitations of T.O.M. Some of these ideas have to do with controlling and distorting the memory of the spectator, about which Juan Tamariz offers much thought-provoking analysis and technique in his recent theory opus, The Magic Rainbow. The astute and careful student will find that the teachings of Tamariz and Close may be productively utilized when considered and applied together.

Michael Close is a worthy mentor and theoretician who has added yet another significant tool for students and fans to add to their already burgeoning Mike Close toolkit. Make room.

The T.O.M. Epiphany by Michael Close. E-book; 43 pages; illustrated with color photos and links to instructional videos; 2019. Published by and available from the author, $24.95.

A Secret Has Two Faces

By A. Bandit

Most people reading this will already know who Derek DelGaudio is, one of America’s most original and talented young magicians and performing artists, and among other things, creator of the hit Off-Broadway show, “In and Of Itself.”

On the other hand, fewer readers will know of A. Bandit, the purported author of this book, which was published in January of 2018. “A. Bandit” is actually the name of a “performance art collective” that was formed in 2010 by DelGaudio and the conceptual artist, Glenn Kaino. Much of the work these artists first jointly created occurred in the worlds of conceptual and avant-garde performance arts, well off the radar of the magic world—artistic movements that DelGaudio inserted himself into as an alternative to the conventions of contemporary conjuring, even while he collected two consecutive awards from the Academy of Magical Arts (Magic Castle) as Close-up Magician of the Year in 2011 and 2012, and then Magician of the Year in 2016.

This is a handsomely produced volume–a coffee table book of sorts. The title offers itself up to many possible interpretations which, at very least, include the fact that two creators comprise its singular author’s name (that explicitly appears within the book as a voice in a conversation with David Blaine). At the same time, the title also conveniently represents the two worlds its contents reflect: the worlds those two creators come from.

Thus, amid its eight contents sections of Essays, Beliefs, Sites, Labor, Witness, Utility, The Out-of-Focus Group, and Shows, magicians will recognize certain names present in essays, interviews and conversations by or with the likes of Max Maven, Ricky Jay, Teller, and David Blaine. And doubtless, readers coming from other artistic universes, and who may be encountering those magicians for the first time, are likely to be more familiar with the names of other subjects who appear in the book’s discussions, including not only Kaino, but also Marina Abramović, John Baldessari, and Tony DeLap.

Much of the book serves to record and report on many of the A. Bandit artworks circa 2010 through 2017, including their first public performance, “The Space Between,” and also describing one work that was conceived, but never finalized into exhibition form. These accounts are largely graphic in form, and lend the book its compelling visual qualities.

Frankly, A Secret Has Two Faces, while beautiful, sometimes fascinating, and occasionally abstruse, does not lend itself well to an exhaustive review, which is probably the reason that there are few, if any, substantive reviews to be found; it’s certainly the reason why it has taken me this long to compose anything myself. This brief item is not intended to give the book short shrift—the risk of that interpretation has frankly served as my most serious concern and cause of the ensuing delay—but rather, I have now come to believe, reflects the very nature and intended purposes of the work.

I would say this: A Secret Has Two Faces is a beautiful book, and is as unusual as the two artists who collaborated to create its authorship, namely A. Bandit. It’s an informative book, that lives in its best service as a multi-faceted work that attempts to bring two divergent subjects together, namely conjuring and conceptual arts. As such, it provides more about the latter than of the former. For magicians, I think that makes the book particularly useful, as it may open a doorway to non-traditional avenues of artistic expression, for an art form that is often hidebound by its traditions.

For the audience already familiar with the likes of Kaino and conceptual art, the book is probably less informative about the art of conjuring, but this is merely an observation, not necessarily a flaw. There are other sources and guides by which to discover and explore the art of conjuring.

Above all, perhaps, A Secret Has Two Faces helps to further reveal to us the mind and artistic inclinations of one of magic's unique and favorite sons, Derek DelGaudio. For that, if for no other reason, it should earn its keep on the shelf—or coffee table—of any thoughtful and curious conjuror.

A Secret Has Two Faces by A. Bandit. 10” x 7½” cloth hardcover with silver foil stamping; extensively illustrated; 2018. Published by Delmonico Books-Prestel. Available at Tannen’s Magic, $95.

The Ultimate Ten-Card Poker Deal

By David Malek

David Malek is a sleight-of-hand close-up magician and gambling expert who has published little of his work, and is not widely known in the magic world, beyond the borders of California where he resides, and the halls of the Magic Castle where he has long performed (albeit in on-and-off-streaks throughout the years), and where I first met him in the early Nineties.

The first time I encountered him, he was performing at the Castle in the Close-up Gallery where he was doing a gambling demo act that featured two overwhelming elements: first, some of the best riffle run-up work I had ever seen; and second, an arch, larger-than-life character, as if he had stepped out of “Guys and Dolls” and sat down at the card table. Needless to say, I loved what I saw.

The deliberate meta-joke of that character, and of the fuzzy borders of where its line might fall between truth and deception, is a "joke" that not everyone always gets, and that can turn some people, especially magicians, off. To me, and to countless audiences I’ve witnessed firsthand, the results—particularly in the guise of his more current persona as "The King" (a running reference throughout his act)—are captivating, and hilarious. The reason I agreed to write the introduction to the first of these two small booklets, The Ultimate Ten-Card Poker Deal, is because I first saw the author perform this routine at the Castle, accompanied by a friend of mine, a talented actress who likes magic and is extremely discerning in her tastes. I took her to three excellent shows at the Castle that night. Malek’s was her favorite, and I understand why. He closed with the routine at hand and had us both screaming with laughter, and at times, all but out of our seats and on the floor. We weren’t the only ones.

I mention these facts in the book’s introduction. I also mention that of all the countless versions of the Ten-Card Poker Deal in print (including those among the massive collection, the Bammo Ten Card Deal Dossier compiled and written by Bob Farmer), this routine stands out as notable in several worthy respects. For one, it contains as many as seven phases, if you choose to utilize the entirety, including a final phase in which the cards are torn in half and the effect is still achieved. That length probably reads as ludicrous to many if not most readers, and I would likely be skeptical myself if I hadn’t myself seen the routine performed live. Each phase serves a purpose and, as in any well-constructed routine, each phase rises in interest and audience engagement. What’s more, the effect becomes increasingly mysterious. Despite the fact that (or perhaps, because) the Ten-Card Poker Deal is a sleight-free trick, Malek’s handling manages to put the secret, as it were, into the spectator’s hands, twice, in turn serving to cancel the method even further than in many other versions.

While it may seem a hyperbolic, over-the-top-claim, the title of The Ultimate Ten-Card Poker Deal—indeed, like other aspects of David Malek’s persona and performances—the word “ultimate” might actually be appropriate in this case. This is a mystifying, entertaining, multi-phase routine that can close an act—a routine with which you can apply all of your focus and attention to the performance, and to your relationship with the spectator and audience, rather than to executing challenging methodology. All of this, and more, is explained in exquisite detail by the author, who provides not mere instructions, but a true lesson in constructing a routine, and learning how to perform it. It’s the invaluable depth and care of that lesson, above and beyond the power of the routine, that makes the asking price more than reasonable. Skip buying the next instant download and buy a genuine lesson in magic and showmanship.

The Ultimate Ten-Card Poker Deal by David Malek. 6” x 9” softbound; 68 pages; illustrated with black-and-white photographs; 2016. Published by the author. Available at Vanishing Inc., $29.95.

The Dream Card Revisited

(The Ultimate Card to Wallet)

By David Malek

Everything I’ve written about The Ultimate Ten-Card Poker Deal is equally true, if not more so, of The Dream Card Revisited. This booklet also addresses a single routine, at a slightly higher price than that asked for the Ultimate Ten-Card Poker Deal. In return for that slight difference, you get a book twice the length, that is nothing less than a master class in conjuring thinking, given by a master magician. That’s right: one hundred and fifty-eight pages dedicated to one routine. And a book filled with priceless teaching.

“Teaching” is the operative word. You don’t just get the instructions to a trick. You get every conceivable detail, and I cannot imagine a student completing study of this book and feeling that anything has been left out or any unanswered questions are left to linger. There are, for example, thirteen pages devoted to palming, describing multiple techniques, countless fine details, and superb theoretical discussion about misdirection, along with the author’s thoughts about other palming experts who have influenced his work, including the legendary Michael Skinner, and a contemporary, John Carney.

“The Dream Card” is a neo-classic take on the card-to-wallet plot, devised by Darwin Ortiz and first published in 1988 in his first and excellent book, Darwin Ortiz at the Card Table. It remains among his best-known routines—and for good reason. It brings a different approach to the standard card-to-wallet routine, invoking not just the effect of transposition, but also of a kind of time travel (not unlike Alex Elmsley’s “Between Two Palms”). The routine achieves a deep mystery with fairly minimal requirements: an extra card; a force (in Malek’s version); a palm; and a Balducci-style wallet. The original routine has been used by countless magicians (I’ve used it myself on the trade show floor), and it’s sparked variations, notably including Jim Swain’s terrific “Airmail Card” (Miracles with Cards by James Swain; 1996).

Malek considers Ortiz’s trick to be “a one-of-a-kind brilliant card trick,” that he has been performing professionally for more than twenty-five years. In that period, the author has devised a number of “ideas that preserve the effect while, at the same time, make other areas of the routine stronger.” I believe these claims are accurate, and reasonably made—grounded in real-world experience, not armchair theorizing, or vaporous wishful thinking of the kind that fuels the instant download market.

Purchasing this book will deliver a reputation-making, career-supporting, miracle routine to your repertoire—assuming, of course, you put in the necessary study and practice, and all-around effort required. But that’s not why you should buy this book.

You should buy this book because David Malek is both an excellent thinker, and an excellent teacher. When I think about some of the greatest influences, teachers, mentors, and colleagues I’ve known in the course of my life in magic, the one thing they all had, or have, in common, is the level of detail in their thinking. Dai Vernon, Johnny Thompson, Michael Skinner, Tommy Wonder, Juan Tamariz … these men, and others like them, have expanded my thinking—about not only what to think, but also about how to think, and about what is available to think about, and is worth thinking about. Every phone conversation, letter and phone call I ever exchanged with Michael Skinner served to further expand my universe of thought about magic.

That’s exactly the level of detail you get in The Dream Card Revisited. This isn’t just a book about a trick; it is a guided tour and a teaching course in expert thinking about conjuring. I believe, above all, that that is what you stand to learn from its pages. And that’s the kind of lesson that is impossible to put a price on.

The Dream Card Revisited by David Malek. 6” x 9” softbound; 158 pages; illustrated with black-and-white photographs; 2017. Published by the author. Available at Vanishing Inc., $34.95.

SEE LYONS DEN INDEX