Submitted by Jamy Ian Swiss on

The Magic Rainbow by Juan Tamariz

Reviewed by Jamy Ian Swiss

“Luckily, easy tends to be the opposite of art.”

—Juan Tamariz, The Magic Rainbow

On just a few occasions in my life, I have read a book of conjuring theory that has energized me, inspired me, opened my eyes, and taken my breath away. The first time that occurred was when, in my twenties, I read Our Magic by Maskelyne and Devant. Maskelyne’s passionate plea for magic as art, combined with penetrating analytical thinking, was revelatory to me. Years later, in one of our earliest conversations, Dai Vernon commented to me, much to my surprise, about our shared regard for the book.

Later in my twenties I began searching for a copy of Neo-Magic by Sam Sharpe. The first version I read was a photocopy, and it opened my eyes to new ways of thinking about the art of magic, and to a system of classifying effects that I have utilized ever since. The book mesmerized me.

It has been many decades since those discoveries. Certainly I have read inspiring and instructive books since. But I was reminded of the genuine excitement of those two particular encounters when I read The Magic Rainbow. Months ago, when sitting at the computer I first began to read an advance digital copy, my partner, Ann, called out to me, “What are you reading? You must really like whatever it is!” How did she know? Because she could hear my gasps and exclamations as I started to read the first chapters. From the opening pages, I was energized, riveted, enchanted.

Juan Tamariz explains that, “This book is little more than a mosaic made of articles and essays I’ve written throughout a period of almost forty years.” And indeed, I feel like I’ve been waiting forty years to read it—or at least thirty, since I first saw Tamariz perform, in the Forks Hotel at the Fechter’s close-up convention. In the three decades since, I’ve had the good fortune to see him perform in multiple countries, including in shows for the public in his native Spain; I’ve attended his lectures and workshops; and I’ve had the pleasure of sharing meals and personal conversations with him. Across those same decades I have become a passionate appreciator of his work, his artistry, his writing, and also, of the real person behind it all.

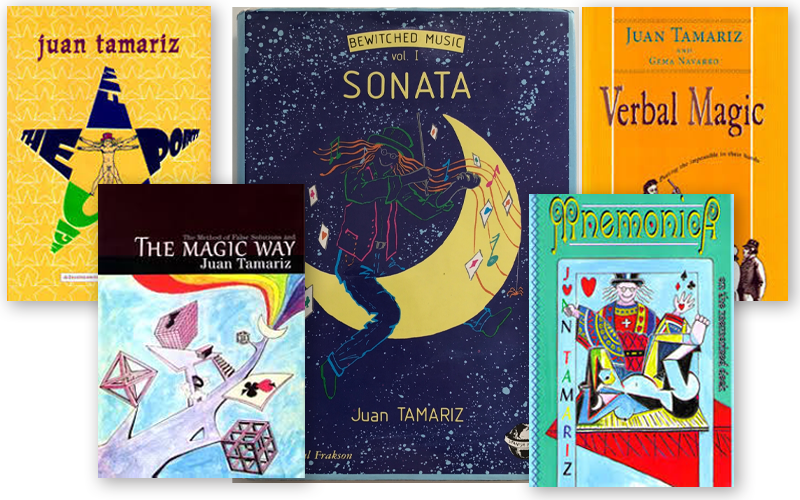

I have studied all of his published writings in English, from an early lecture-notes edition of The Five Points in Magic (circa 1978), to multiple editions of Sonata, multiple editions of The Magic Way (including its latest iteration published in 2014 by Hermetic Press), Verbal Magic (in English, 2008), and of course his technical masterwork, Mnemonica (2004), one of the most internationally influential books of card magic to appear in my lifetime.

But I was also painfully aware that Tamariz was continually writing and publishing articles, essays, books and monographs in Spanish that have never appeared in English. I knew that these works existed, and I felt their absence, frustrated in my inability to access them.

And so this is the book I have been waiting for, lo these many decades—and I am here to tell you: I have not been disappointed. The Magic Rainbow is the most profound, extraordinary, and essential works of conjuring literature that I have read in a very long time.

In his introduction, the book’s translator, Rafael Benatar (who worked intimately with editor and publisher Stephen Minch in preparing this volume), provides an apt description of what we find presented between the hard covers of The Magic Rainbow: “What really matters is that you have here a rare opportunity of looking with a magnifying lens into the mind of a genius, who allows your inspection and invites you to do so. He hangs it all out in these pages, just about everything he thinks, every opinion, everything he has mentioned in conversations over the years, everything he has learned, although it’s easy to imagine that the process goes on forever.”

What Benatar says is true, and thrilling. The word “genius” is all too casually tossed about these days, but in Tamariz’s case, the term is more than apt. The depth of his thinking, as represented in books like The Five Points and The Magic Way, reveals a mind not merely obsessed with magic, but one fascinated by an eclectic range of art, influences, and ideas. He constantly examines these sources to help penetrate ever deeper into the mysteries of his own art, trying to uncover ever greater and more useful theories, which he in turn puts to thorough work, first and foremost, in his own performances.

And from his personal practice, he preaches his beliefs and offers his theories, so that other practitioners, and the art as an entirety, might benefit and progress. Just as his performances come across as joyful acts of love, so does his writing, which reveals his passion at every turn of a page.

As Tamariz observes, The Magic Rainbow is a mosaic, a collection. The material was not written with the intention of a book, and it does not read as a perfectly integrated, uniform work. There are even a handful of older pieces that do not entirely reflect where Tamariz would eventually land in his thinking, but that he clearly identifies are included for historical perspective. Yet any impression of a pastiche was a rare and quickly passing one for this reader. The book, organized into twelve chapters with three appendices, holds together as a massive work of both theory and practice, and also as an artistic manifesto. Tamariz shows us his heart and his brain, and provides an instructional manual that has the potential to improve any and every magician’s work—and, I dare say, of making good magicians into great ones.

The book begins with a chapter entitled merely, “Magic,” consisting of seventeen short entries totaling forty-three pages. I have heard that some readers find these early pages challenging, with their ephemeral quality and poetical discussions of the nature of art, craft, and of magic itself. This was not my experience, however, for these early pages are the ones that made my partner wonder, from two rooms away, what I was reading. Here is Tamariz attempting to answer his own opening question: What is magic?

An extremely complex art that demands control of fingers, hands, body, voice, eyes, words and psychology; an extremely beautiful art that speaks of myths and symbols (with the depth of play), that enchants and haunts and fascinates and excites every layer of the brain, that brings us headfirst into mystery, that speaks to us of desired dreams—that imitates, not the human being as does theater, not the interior rhythm as does music, not the trill of birds as does singing, not nature (landscapes, people, sensations) as do painting and sculpture, not dreams as do movies. Instead it imitates the power of the gods (no less): the fascinating total art of magic.

In the ensuing nearly six hundred pages, Tamariz will deconstruct every idea, and nearly every word, of that pregnant paragraph. He will explain and justify his conclusions, discussing the role of myths and symbols, of play, of mystery, of dreams, of the differences between magic and traditional theater and other performing and narrative arts, and of the requisite element of fascination. The ideas are visited and revisited from multiple vantages, turned this way and that, allowing us to consider their complex interplay in Tamariz’s theories of what magic is, how to create it, how to perform it, and how to create the best experience for the audience. It may not be an easy ride—“luckily”—but I found it an exhilarating and provocative one.

This opening segment also explores the author’s ideas about what makes magic an art—and more particularly, what makes some magicians good artists. He focuses on the nature of art as self-expression:

…I think that to elevate magic to an artistic level, the first requirement is that the magician believes in his magic as art and tries to express himself through it. To express himself, not just to be liked, and not just to fulfill the wishes of his audience for amusement and entertainment, regardless of how well that is accomplished and of how highly interesting that function could be in the context of our vital and social destiny. And of course, the richer our inner world, and the more intensively and harmoniously that inner spiritual world in us is expressed, the higher the artistic quality our beautiful, mysterious and symbolic magic tricks will have: a quality they will acquire—as if by magic. …I believe… it is the will, above all, of the author, the creator, the performer, that transforms, through his wish to express his inner world, a performer into an artist.

In Chapter 3, “The Magical Effect and Its Significance,” Tamariz offers an important essay entitled “Symbols: Magic and Symbolism.” Although I have, through most of my adult life in magic, been deeply interested in this subject, and put it to constant consideration and use in my work—influenced by, among others, magicians and theoreticians like Peter Samelson, Eugene Burger, and Robert Neale—I find Tamariz’s work here to be, by far, the most comprehensive and, in fact, accessible for practical application. For those unaccustomed to thinking in these terms, he lays out a remarkably thorough and methodical discussion, exploring his theories and making a case for their usefulness. In this opening look at the subject, one to which he will return throughout the text, he asks, and answers, why the cut and restored rope, despite its typical methodological weaknesses, has long had such great appeal for audiences. He looks at why black Egg Bags are better than plaid, and why eggs are better than other objects to use in that classic trick; why the Coin Assembly should be done with four coins; and why the Reverse Assembly plot has so little magical strength by comparison to the more linear effect. (Many would disagree, but I am not one of them.) And he also examines the Ambitious Card plot (acknowledging the limitations of that symbolically mistaken title), and why—in symbolic terms—it possesses such longstanding appeal both to laymen, as well as to the magicians who perform it for them:

The selected card, after having been lost in the deck, rises (ascension); ends up on top of the others (power); loose, not trapped (liberation); and in view, not lost and anonymous among the others (individualization). The Fulfillment of those four wishes, reaching us via symbolism, affords the trick massive allure. We love it, we enjoy it, and that’s why we want to experience it again, to feel again and again the great inner satisfaction, the joy, the beauty and the overall fascination.

In discussing the significance of symbolism in magic, he circles around again to another descriptive definition, gradually assembling the various building blocks that magicians gather and eventually use to create magic. I am reminded of my friend Patrick Watson—Canadian documentary filmmaker, television personality, writer and amateur magician—often saying to me that the purpose of the art and craft of the essay is to “gain assent” of the reader. The Magic Rainbow comprises countless textbook examples of the form, because while Tamariz approaches his subject with love, he is also constantly presenting supporting arguments to the reader in order to sway him or her toward assent:

The true beauty of magic doesn’t lie, or perhaps just lie, in graceful execution; or in staging; or in the aesthetics of decoration, lighting and costumes, or in the comedy or poetry of the patter. It is rather a combination of the logical impossibility of the effect with the fascination it produces. Above all, it grants and fulfills the experience of an impossible dreamed wish, making it feel possible. And that sensation often comes to us in metaphoric form, through implicit symbolism.

But make no mistake: Tamariz’s intent is to provide you not just with theory, nor mere argument, but also with practical tools to assist performers in making their journey as artists. In this same chapter—only the third so far of twelve—he provides seven pages to serve as “An Example of a Practical Application of the Theory of Symbolic Magic” as it applies to “The Magic of the Spheres,” namely, billiard ball manipulation. Here is number seven of twenty-seven pieces of advice offered:

Practice with somewhat larger balls than those you are going to use. And practice without hand cream. The real performances will then be easiest. Do the riskiest and most difficult moves in rehearsal. Practice at a faster pace. Execute the routine while talking to someone or watching TV. Go through the motions only, without props. Rehearse mentally in the subway, on the beach, in bed. Practice to make all gestures and movements second nature, until the routine happens by itself, but avoid over-practice, the point at which you don’t feel what you’re doing. You do it because you can, but it becomes boring.

This is followed by a careful three-page analysis of one of Tamariz’s signature performance pieces: “El Cochecito,” his marvelous routine for the Koornwinder Kar. [You can see a performance of this in Take Two #66] For me, it is always a treasured opportunity when a world-class professional deconstructs one of his most beloved and long-performed routines. This is one of several such special examples to be found in the pages of The Magic Rainbow.

While still in this content-laden third chapter, Tamariz discusses the nature and importance of the effect, in four short but substantial essays, the first of which is entitled “The Fascinating Effect.” Here, he speaks to one of the defining elements of his work, namely, his uncompromising demand of performing only powerful effects, with genuinely impenetrable methods:

An effect is magical because of its impossibility. Therein lies the beginning of the authentic beauty of a magical effect: It should be impossible, and the more impossible it is, the more beautiful, the more artistic, the more magical it will be.

It should be astonishingly impossible. Its impossibility should transport us to another dimension. It should be so strong, so powerful, that it tears your logical structure apart…

I think one can never insist enough on this point. The power of the logical impossibility, I repeat, is the unique quality of our art. Without it, without that requisite, we are not, I feel, in the domain of magic but in those of other arts (whether they be mime, drama or dance). They are as respectable, as desirable, as beautiful, but still they are not ours. The logically impossible is as essential to our magic as music is to opera.

There is still more invaluable advice and insight in this third chapter, one of my favorites of the book, but let’s move on to “Chapter 4: Magic and Memory.” I have long been fascinated observing Tamariz’s constant efforts to control the memory of his spectators, both during and after the performance. In this section he provides a remarkable amount of detail about the results of his study of memory, and how to use and manipulate it through performance. There are many pages of practical and specific advice here in his examinations of “Encoding What is Perceived” and “Evoking Memories.” In this latter essay he introduced the idea of “The Comet Effect”:

There is a bright point, the effect as perceived by the spectator in the first place, followed by a long tail that increasingly grows in size and brilliance, which is the effect as it’s being felt and remembered by the spectator, and which is then perhaps told to others, during its life in the memory, with the passing of time.

Thus the Comet Effect is about maintaining a long-term impact on the spectator’s memory of their experience. Tamariz believes that this enhanced memory that remains with the spectator is in fact “…just as truthful as the one adhering more closely to reality… what is narrated is actually true, because it is with what the spectator feels, built on what he felt and then improved on while evoking it.”

This lengthy chapter also revisits and further analyzes a routine from Mnemonica, one of the greatest routines I have ever seen Tamariz perform—a piece so beautiful in its thinking and perfection that when I saw him perform it in 2004, it literally brought tears to my eyes. Although he has discussed this routine elsewhere, including elements that have baffled countless magicians, here he breaks down the role of memory in designing this routine’s effectiveness and lasting power, utilizing a system he dubs “The Mnemosyne Staircase.” With this model, “the following three proposed objectives are accomplished: (1) Reinforce the memory of positive conditions… (2) Cause negative conditions to be forgotten and (3) Cause what never existed to be remembered…” Tamariz’s memory toolkit also describes and explores the use of “Emotional Erasers: an Encoder and Eraser of Short-Term and Long-Term Memory,” and “the Work of the Magician after the Session [performance].”

In short: This is not pie-in-the-sky bloviating (a good description of much of current mentalism literature). Rather, this is an instruction manual for making miracles.

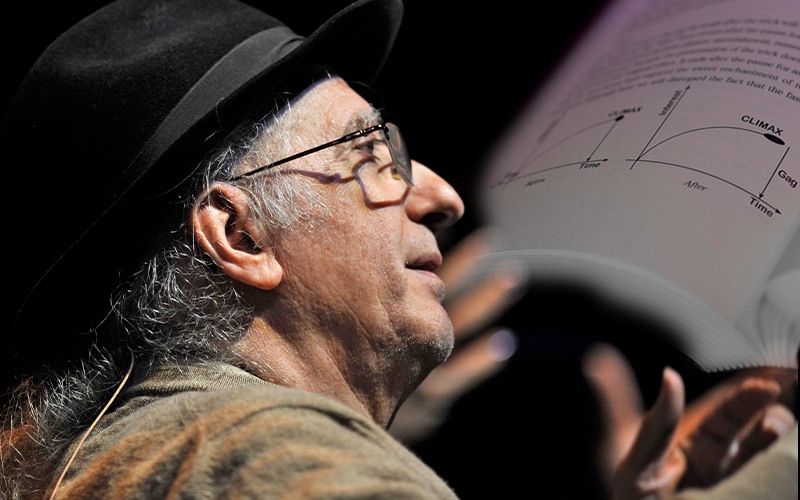

Chapter 5, on “Dramaturgy,” includes the use of emotions, timing, rhythm, and patter. Importantly, it also addresses how to manage the unresolved conflict that magic creates in the spectator’s “logical-rational” mind. Magicians of any reasonable experience understand that the dissonance spectators experience in the face of magic is a force to be reckoned with—simultaneously both positive and negative—and there are many possible paths by which to nurture the positive and minimize the negative. Many magicians are simply terrified by this dissonance, and avoid it at all costs, preferring to do weak magic, which they further demean by their own attitude, rather than face the spectator’s potential discomfort—the very thing that gives magic its most distinctive power and impact. (Magicians who above all wish to always please the audience, constantly seeking nothing but their affection and desperately avoiding all other possible emotions and reactions, frequently follow this road to its logical conclusion, eventually arriving at the professional status of “hack.”)

Tamariz first reviews his fundamental vision: “…for me, the art of magic is the art of showing the impossible and the wished for—which is to say, of the impossible and the fascinating—as possible. It deals with presenting something similar to a secular miracle; something wished but impossible that is shown as possible and made possible in artistic reality, and that fascinates us, charms us, astounds us. It’s something we long for, although it is impossible to achieve, because it is prevented by the laws of nature and of physics: levitation, resurrection, learning the future, changing the past, etc.” He then makes this concluding pronouncement: “It is precisely that conflict between the wished for and the impossibility of experiencing it that is solved through magic. The magical effect makes the granting of the wish possible by breaking and overcoming the laws of nature; and in a certain way, as we will see, it solves the logical-rational conflict, providing a greater sense to magic. It’s a secular miracle.”

Thus Tamariz believes that, if the magic is strong enough, the performer’s attitude sufficiently artistic and empathetic, it becomes the very experience of magic itself that serves as a resolution of the spectator’s cognitive dissonance. “The conflict of the symbolic wish is resolved through the magical effect that brings it to life.”

These brief quotes are merely excerpts from the extended argument that Tamariz presents in support of his theory. This segment comprises a hundred pages, and at that reflects only a portion of the fifth chapter on dramaturgy. I found it a riveting conception, an explicitly articulated solution to a subject that countless magicians have faced and considered.

There is much more to this section as well. Tamariz discusses the differences between “Two Levels of Reality: Presentation and Representation,” concluding that there are critically important differences between magic and narrative fiction. He writes, “So, magicians are people, not fictional characters, who present something apparently impossible and pretend to have supernatural powers.” And in a related thought concerning the idea of character, he believes that, “…in magic, I don’t believe much in the ‘creation of a character’ for performing and representing, but rather in the selection of authentic components of our personality, not invented ones, to showcase our persona as we like or wish to convey and express it through the art of magic: the selection of tricks and effects, of gestures and attitudes, of words and their intonation, of the relationship with our assistants or with the assisting spectators, etc.”

An eighteen-page discussion of timing and rhythm includes “The Beloved Art of the Pause,” in which are described and analyzed techniques, both theatrical, deceptive, and misdirective, that include, “The Prior Pause, the Posterior Pause, The Initial Pause, Resting Pauses, [and] Relaxation Pauses.” Similarly, a discussion of timing includes, “magical timing, synchronous timing, opportune timing, the opportune moment, and the “beat trio of strong-weak-strong” timing.

This segment also brings the author to expressing a thought about Dai Vernon’s masterpiece, “Triumph” (one I long ago came to believe as well), namely that, in Tamariz’s words, “It is my opinion that this trick can have the same impact (or more), magically speaking, if the [original Vernon] story is omitted, because of the enormous symbolic power of the effect, which takes it to the peak of an artistic Olympus: triumph over chaos.”

This clarifying and understanding of what kind of fiction magic is—that is a game of pretend that the audience is aware of as it unfolds, including being aware that the magician is aware of his own pretense—serves to clarify what renders magic unique among the performing and narrative arts, and at the same time, distinguishes it in important ways. He writes, “For me, close-up magic, generally speaking, is an eruption of art into life, of the magical, the impossible wish, into everyday life. It’s not so much a show (though partly it is, of course) as it is a unique experience. That’s why most of the time it is performed— and I think it should be—with everyday objects…”

Regardless of where each reader may fall in considering these ideas, again, Tamariz also provides a wealth of utilitarian guidance. In a discussion of his version of the Six Card Repeat, a pet effect that he often uses to open shows, he explains “…how I prevent the presentation of the trick from becoming canned or automatic, also adding variations in patter, which I attempt to do, at least slightly, in each performance.” This is an excellent and practical guide for how to avoid a major pitfall that all magicians are constantly in danger of, namely the appearance of a rote performance.

As Tamariz heads toward some of what I consider to be the most invaluable and vital ideas of the book—his models of the “Seven Veils” and his “Magic Pyramid”—he makes a critically important statement about the role of presentation in magic.

I believe that the effects of great magical quality can stand by themselves. They don’t need additions or presentational patches, which is to say non-magical, external aids. The magic itself, totally impossible and wonderfully fascinating, in its total naked purity, will make spectators’ most beautiful and sensitive strings vibrate. Those vibrations will be the magical meaning of the effect (its symbolism), its nature as secular miracle (as a lived and granted dream), and will impregnate the deep experience of the spectator (and of the magician) with artistic harmony and beauty.

This doesn’t mean that some magical effects—or under certain circumstances, all magical effects—could not benefit from some type of external enhancement (music, patter, gestures…). As long as they are treated with the delicacy and care such magical effects deserve, and with the discretion and rigor artistic purity demands.

An aside: About fifteen years ago, Tamariz came to the U.S. to serve as an artist in residence for several days as part of the Theory and Art in Magic program at Muhlenberg College, organized by Lawrence Hass. (I spent much of those four or five days visiting and sharing meals with Tamariz when he wasn’t working; two years later I would appear in the same artist-in-residence role for the program.) On the same tour he also presented lectures for magicians; the first stop was in New York City, and the day after that lecture, I received a phone call from a friend. “Tamariz says presentation isn’t important!” he announced. I thought for a moment, and wondered about the context. Tamariz can be a deliberate and self-aware provocateur, and this was one of the most provocative statements from him that I had ever come across. I knew he had to have a deeper intent.

When I saw the lecture myself not long after, I learned the rest of the context, and that context eventually came to be framed in Tamariz’s Magic Pyramid (which differs from the Magic Pyramid theory of Tamariz colleague, Roberto Giobbi). It’s not that he is claiming that presentation is unimportant. Rather, he believes that while ordering the importance of the elements that critically contribute to effective and artistic magic—persona, effect, method, emotions, and presentation—and acknowledging that all these elements are terribly important, presentation is the least important one of the list. And further, he also advocates that the priority occurs precisely as I have just listed them, with the personality of the performer being the most important of all.

While it took me a period of time to consider these claims, over the years I have come to firmly agree with the maestro. Even though I sometimes use heavily scripted presentations (particularly on stage), and even though I occasionally include storytelling or lengthy monologues in my own work, my overarching perspective is that elaborate, extended presentational and production elements more often do more to damage magic than to assist it. I believe, with Tamariz, that the personality of the performer is foremost (and when he uses the term “persona” he distinctly does not mean in the theatrical sense of a constructed persona; rather, whenever you see the word “persona” in these pages, you should read it as “personality”), and that presentation comes last on the list.

In Handsome Jack, etc. by John Lovick, the author takes a survey of a handful of professional performers (including this writer) about this very subject, asking them to prioritize a similar set of elements. It is very interesting to see where these performers differ in their conclusions, and readers’ opinions might differ as well. But Tamariz presents these issues and argues for assent, and the result is a provocative, enlightening mental conversation between writer and reader—a conversation I found thoroughly arresting, one he revisits in multiple instances throughout the text.

Elsewhere Tamariz discusses why creating false realities for the audience to believe in is both an ethical and aesthetic problem; why and how creating a false story with, for example, fake claims of mental powers, is a kind of cheating, while observing that, “The deception creates a stronger impact and it’s easier. The artistic truth causes a different emotion, more difficult to attain, more beautiful. …The eternal drama of love and death in a work of fiction: the extremely difficult and beautiful art. The other thing is a scam. An easy and ugly scam.” This is a subject about which he clearly has strong feelings and beliefs, which he mentions at various times, but the aesthetics are as important to him as the ethics. In a footnote mere pages into the book, for example, he opines, “…fair play should not admit low blows. Stooges and marked cards are low blows, because the spectator, aware of their existence, doesn’t protect himself against them. Those are implicit rules of the game.” This of course is more purely an aesthetic position, albeit strongly held, whereas his thoughts on psychics and mentalism are founded in both artistry and ethics alike.

I must confess to finding myself occasional pleased at instances when I found the maestro’s thoughts to echo subjects and ideas I have myself written about in the past. I hope the reader will indulge my quoting this one example, a notion that I wrote about in my first book, Shattering Illusions, in 2002. Here is Tamariz’s take in The Magic Rainbow:

Ever since I began in magic, I have observed with some surprise how one can get to know people from their reactions to magic, to the impossible and illogical. It turned out that, knowing some people only superficially, I discovered from their reactions when doing magic for them a certain way of being and behavior that they had kept hidden, voluntarily or not, in their every day lives. I thought, and continue to think, that magic—the experience of the logically impossible—acts as a project test (like the Rorschach Test with ink blots) that puts the spectator in a situation for which he has no learned pattern of behavior. …Through this thought process, he shows himself more truly. I can sometimes get to know a person better by showing him some magic than by having a couple of beers with him and chatting for hours.

True dat.

In Chapter 9, “About the Construction of the Session,” Tamariz provides enormously practical specifics about how he builds his own performances, including approaches to a “routine” (“a series of several tricks”), an “act” (“a performance of at least ten to fifteen minutes”), and a “session or show” (“A series of tricks and routines in one or more parts, with an intermission.”) He provides details such as where he places “El Cochecito” in a program and why; and why he always designs a program with an odd number of tricks. And he also explains how he constructs his stage performances, and what portion of the material is selected spontaneously, to wit: “The moment the curtain opens and I walk on stage in front of the audience, I don’t know which tricks I am going to do or in what order I will do them. Sometimes—except for the first rick, of course, which I carry in my mind and my hands—I have no idea!” I have known about this aspect of his work for many years, but it still never fails to amaze and impress me. In this section as elsewhere in the book, he is quick to point out that when it comes to the aesthetics, he is explaining what works for him, from his perspective, in his own shows, and that the reader’s experience, opinions and conclusions may differ.

In Chapter 10, “Creating Illusion,” Tamariz includes details of his longstanding approach to using projection video when performing close-up magic on stage, a challenge that I frequently see performers use poorly. Tamariz’s model is, and has long been in my estimation, the definitive working solution.

In this same chapter he discusses the appropriate use of technique, and indeed the very nature of what we mean when we use that term. Positing that someone might criticize the surrealist painter, Magritte, as a poor technical painter, Tamariz offers a contrary perspective. “Magritte perfectly manages to convey to me his conception of the world through his technical handling of paint. Therefore, he is, for me, an excellent painter.” He then applies this thought to an example drawn from the work of the great sleight-of-hand close-up artist, Albert Goshman. In considering Goshman’s reliance on the mechanical Devano deck in his signature routine for the Rising Cards, Tamariz pronounces it an excellent choice of technique, likening it to Magritte. Thus Tamariz examines the debate about what is meant and understood by the very use of the word “technique,” adding that, “…it is a necessary intellectual debate (perhaps a self-debate) about the notion and function of technique. It requires us to clarify the values of appropriate and well-executed, both essential features of technique.”

Moving on to Chapter 11, “Highly Personal Confessions,” the author takes yet another stab at summarizing his personal unified field theory of magic, what he dubs his “Theoretical Conception”:

Magic is an art, very complex, very powerful.... It is a symbolic art, ritualistic. We play at being gods. We are dreams approaching reality, a reality lying between theater (a reflection of reality in near reality) and film (dreams in images). Magic is desire. It has an inner symbolic meaning communicated at a subconscious level. It’s a playful art (games), very technical and demanding of diverse skills: voice, gaze, body, digital technique, psychology… It is addressed to the pre-logical child (play), to the emotional youngster (mystery) and to the reasoning adult (impossibility). It fights and temporarily beats reason, forcing it to give way to fantasy and imagination. It is an art of communication and love. It consists of a complex technical and structural skeleton, of an emotional and dramatic embodiment and of an impossible and fascinating effect. The magician is not an actor. He is himself playing at being a magician. He is the guide of spectators who are not mere spectators but spect-actors and co-participants. The objective is The Rainbow of illusion and beauty, which is not a part of reality (although it is). One should be a good guide (using the Five Points) and lead the spectators down a good path, making sure they don’t get lost (The Magic Way: saying “No” to the true solutions or to the false ones believed to be true) and that they reach a truly fascinating Rainbow.

Briefly implied in this quote is Tamariz’s dispute with the iconic Robert-Houdin quote about the magician as actor, and elsewhere in The Magic Rainbow, Tamariz expands more explicitly on his argument. In the course of his discussions of the differences between traditional theater and magic, he makes his position clear, as well as compelling.

The twelfth and final chapter, of “Nostalgia,” includes a pair of older essays about “The Spectator Facing Magic” and “The Spectator on the Other Side of Magic,” musings about how spectators should ideally approach the experience of a magic show.

The book concludes with three appendixes that are heavily content-laden. “Appendix 1: Magic and Other Arts (Notes)” includes essays about Magic and Film; Magic and Drama; Magic and Music; and Magic and Painting. I have long said that if you want to be an interesting magician and artist, you must first become an interesting person. Dai Vernon was as eclectic a soul as is Tamariz, and it is wonderful to have him share his thoughts about these many arts that can stimulate and inform our views about our own.

“Appendix 2: Tricks, Symbols and Myths” includes two invaluable systematic lists. The first is “Some Phenomena of Card Magic,” a chart of twenty-two effects itemized and then listed alongside their defining “associated phenomena” and then “myths and symbols.” Thus, for just one example, effect #12 of “Journeys,” i.e., “from one packet to another, from one spectator to another, up the sleeve, to closed locations, little boxes, cases, wallets, etc.,” are associated with phenomena including “miraculous journey; control of space; disappearance and reappearance; invisibility; teleportation; transference of guilt, of gifts.” And the myths and symbols this effect evokes include “Ulysses; Jason; and the magic carpet.”

This list is followed by “Some Classic Tricks of Card Magic,” identifying thirty-seven of the “best effects of card magic” and briefly describing the phenomenon itself, the associated phenomena, and the myths and symbols they evoke. So for one example: Number 31, The Six-Card Repeat, consists of the phenomenon of Multiplication (#8 in the previous list of symbols and myths); is associated with phenomena including “The inexhaustible; richness; multiplication of gifts; life cycle; back to the beginning.” And the myths and symbols thereby evoked include the “Horn of Plenty; the inexhaustible fountain; the eternal return; and the wheel.”

Founded on the extended discussions that precede these appendixes, these charts and lists provide strong tools for thinking about one’s own work and creations, one’s choice of effects, presentations, and the structuring of shows. They are tools of infinite usefulness and potential in the hands of those who actively put them to work.

Finally, “Appendix 3: “Hidden Wishes,” includes a “Wish List of Mankind” in nine categories; and a list of “Wishes and Their Corresponding Tricks,” providing a very lengthy list of tricks, and their associated myths and symbols, organized according to the previously described nine categories.

To me, these appendixes are tremendous tools, not only for systematic analysis, but also as mind-stretching idea generators and creative inspirations. I could not help but think, as I read these final pages, that this material is the opposite of the flat, dull, mechanistic notion of pseudo-creativity represented in the pages of The Trick Brain by Dariel Fitzkee. Fitzkee’s book has helped a few magicians win magic contests. Tamariz’s books can and will help to create great magic, and, I believe, make great magicians.

Juan Tamariz has now written three of the most important conjuring theory books of our time, and of all time. The Five Points in Magic—a manual of craft, detailing the use of the eyes, voice, hands, feet, and body; The Magic Way—a road map of thinking about method, effect, construction, and deceiving the mind of the spectator; and now, The Magic Rainbow—a guided tour of the inner mind of both the magician and the spectator; and simultaneously a challenge to all as well as a personal prayer, aimed at creating the ultimate magical experience. These are works of both art and craft, as well as records of the inner workings of one of the greatest conjuring artists of our time. For anyone who aspires to the performance of magic, they are, in short, required reading. The Magic Rainbow—a book not meant to be read once, but studied for a lifetime in magic—serves as an outstanding conclusion to this landmark, indispensible trilogy.

I’m not going to tell you that The Magic Rainbow is an easy read. It’s not. I believe that in twenty-five years of writing book critique, this is the longest it’s ever taken me to read a book, and to write a review. None of it was easy. But it was… magnificent.

Luckily.

The Magic Rainbow by Juan Tamariz, published by Hermetic Press (and Penguin Magic) 2019. Hardcover 7” x 10” with dustjacket; 594 pages; translated by Rafael Benatar. Available from Penguin Magic $149.

SEE LYONS DEN INDEX